For a long time, small book vendors kept themselves busy by mostly selling works of literature and working with school libraries.

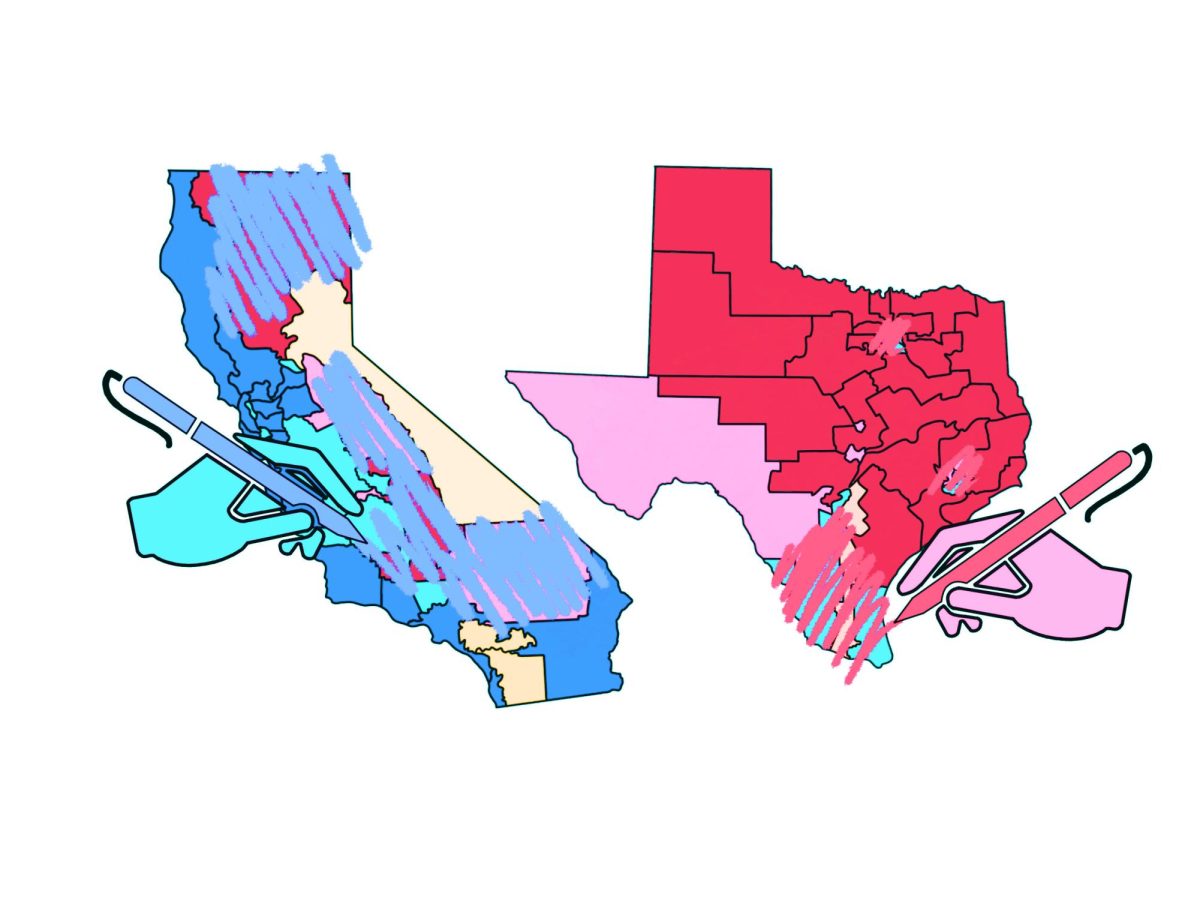

But that all changed when Texas House Bill 900 (HB900) took effect Sept. 1, requiring book vendors to rate every book they sell to Texas public school libraries based on sexual references and depictions.

And that’s not all.

Not only do book vendors need to go through all the books they will sell, but they are also required to retroactively provide an exhaustive list of every book they have ever sold that might qualify for a rating.

“If we had to read every book, it would be very difficult for a small business, which most independent bookstores are, with very small margins,” Children’s and YA Book Buyer at local bookstore Interabang Books Lisa Plummer said. “It would be a huge burden business-wise.”

At Interabang Books, complying with the retroactive clause would be near impossible: the company does not record its sales, calling into question HB900’s practicality.

Plummer believes HB900’s regulations are too subjective to make decisions with such heavy consequences.

“One person’s rating is not everyone’s rating,” Plummer said. “I see no reason in banning anything from anyone’s view. I think that we can trust teachers, parents and students to make up their own minds about how they feel about reading a certain book.”

Director of Libraries and Information Services Tinsley Silcox spent four years earning an undergraduate degree and two years in graduate school studying how to be an information specialist, or a librarian.

Having spent the majority of his career teaching students how to think critically, Silcox said that he and other trained literature professionals are more qualified to make decisions than those without experience and understanding of the content.

Richard Bailey, the education liaison at Interabang Books, agrees.

“This strange law suggests the state of Texas needs to protect students from educators and book vendors,” Bailey said.

Bailey sees that this legislation places individuals who have not studied literature on a higher pedestal than professionals.

“It allows a clear way for people without direct experience with a book to have it removed from classrooms based upon suspicion or bias,” Bailey said. “The power in the rating law lies with people who would rather have books disappear from schools than take the time to read what their children are reading.”

By restricting access to forms of literature, Silcox believes that the building blocks of open-mindedness and social engagement are at risk of toppling over.

“We have to challenge readers to embrace and nurture their thoughts so that they can have personal growth,” Silcox said. “The other thing that is lost when we don’t allow critical thinking is civil discourse. You and I may disagree vehemently about a topic, but I will guarantee you that I will listen to your point of view, reflect on it, and tell you what my point of view is.”

At its core, the bill is supposed to protect younger children and adolescents from potentially inappropriate books not suitable for their ages. But many question the implementation used to enforce the bill.

“The law is purposefully vague and puts unnecessary burdens on professionals who encourage a rich variety of quality literature in Texas schools,” Bailey said.

HB900 regulates the “appropriateness” of books and restricts those who can check certain books out by using a standardized rating system: vendors must rate their material as either sexually relevant or sexually explicit.

Sexually relevant rated books require students to receive parental consent before checking an item out of a library. Sexually explicit, and the book cannot be sold to school libraries. But due to the intervention of federal judge Alan D. Albright the day before being put into effect, the bill has been temporarily blocked, leaving its consequences still to come.

If the law is passed, book vendors and small businesses will find themselves in a difficult situation. Not only will companies have to make the book rating decisions, but they also find themselves confronted by a surging wave of demands, posing potential challenges in their operations.

HB900 is only directed at public schools in Texas; since St. Mark’s does not receive funding from the government, it will not be affected by HB900 or any other similar laws.

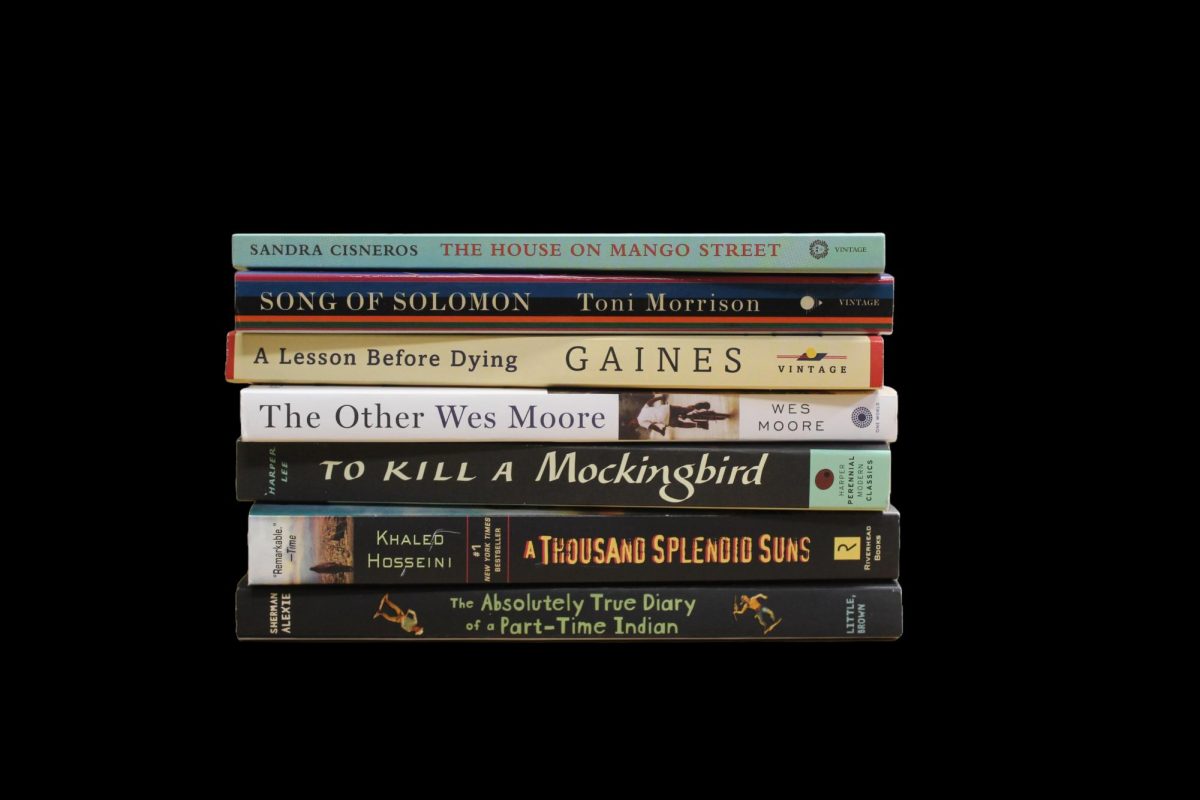

In fact, many previously challenged or banned books like The House on Mango Street, by Sandra Cisneros, and Song of Solomon, by Toni Morrison, have been incorporated into the Upper School English curriculum as core texts.

According to PEN America, a non-profit organization aimed at defending literature, The House on Mango Street was banned in parts of Frisco ISD and the School District of Manatee County in Florida.

But despite the controversy, Senior Master Teacher and ninth grade English Instructor Scott Gonzalez still considers The House on Mango Street, a book about a young Latina girl living in an underprivileged section of Chicago, a book that provides invaluable insight into the world around us.

“The more that we understand the human experience, aside from our own personal experiences, the more understanding, empathetic, and more of a citizen that we will be,” Gonzalez said.

Like Silcox, Gonzalez believes that books allow students to develop critical thinking skills, giving students experiences that they likely never would experience in their lives.

“If we keep children away from the realities of others, then we’re doing them and those other individuals a disservice,” said Gonzalez. “It’s very much like community service. When we ask you to do community service, you are being exposed to different cultures and different socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic backgrounds. And the more you learn to understand where they’re coming from, the better you will be when you encounter them in the public arena.”