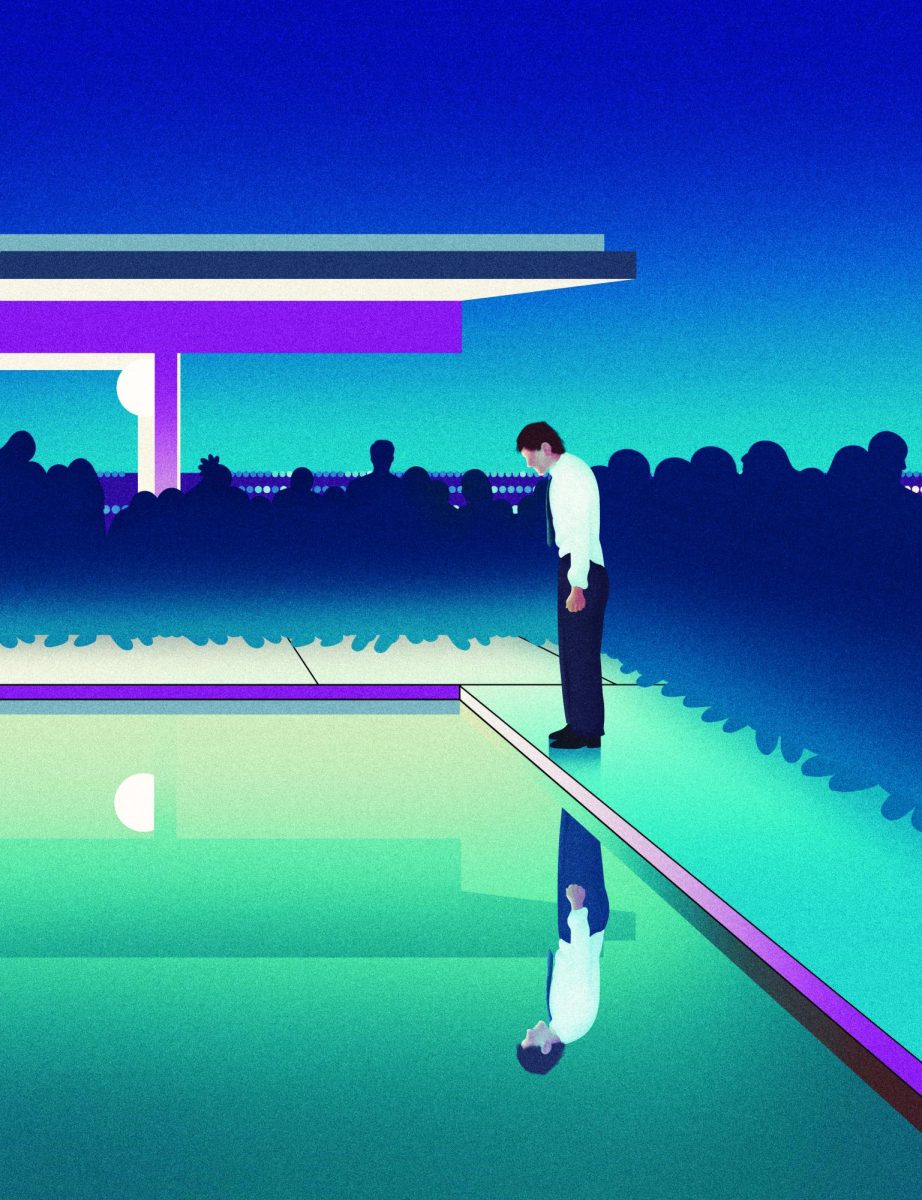

He always had a way out.

Patton Taylor ‘11 was never forced to step in the pool and start swimming laps every afternoon of the week. He could have slept past his alarm and skipped the cold morning swims and lifts. He didn’t need to go to 12 practices a week.

And even after high school, he didn’t need to continue to spend over 20 hours a week pushing through painful swim sets as a water polo player at the United States Naval Academy. He could have dropped out of the sport to help ease the stress of being at the academy. He could have taken the shortcuts.

But he didn’t.

During his time here, former Water Polo coach Mihai Oprea had instilled hard work too deep within him. During his time at the Naval Academy, his college water polo coach had told him that the harder you work, the luckier you get. And always, his parents had told and taught him to never be satisfied.

Everyone faces temptation. Athletes have the choice to not push hard enough on a set. Students have the choice to procrastinate on their essays and studies. Friends have the choice to cheat and ask for the hardest problems on the test.

And sometimes, the pressure and stress of school mounts, and students fall into a vicious cycle.

But with tenets like integrity and honor, the School expects every Marksman to hold off from this temptation. To commit to what it means to be here. To resist this vicious cycle.

Because each student has made a vow: a written pledge to uphold the values that the school defines itself by.

But some get stuck in the cycle. Some are introduced to it. And some just never try to get out.

The Code

At the beginning of every year, each Marksman vows to commit to the values the school holds by signing the honor code.

“The Honor Code was designed to routinely underscore the values and expectations of the school and what it means to be a part of the community,” Eugene McDermott Headmaster David Dini said. “The whole reason to have an honor code is to provide a set of standards that we can hold each other accountable to.”

For Associate Headmaster John Ashton, there’s an expectation placed on every member at school to understand the principle and act accordingly to it.

“It’s up to every individual,” Ashton said. “And I don’t just speak to you guys, because as an adult, you should expect this from me, too.”

But many of those who sign the honor code, however, treat it as a chore and scribble their signature onto a piece of paper without feeling obliged to live by it or to hold others accountable.

Dr. Christian Miller, a philosophy professor at Wake Forest University who studies the philosophy of honesty and has written several books on the topic, feels that the effectiveness of honor codes depends on the degree the honor code is embedded in the school’s culture, rather than its mere existence.

Furthermore, he believes that the honor code, by itself, is not enough to curb cheating and instill the virtue of honesty in students.

One experiment that Miller cites asked participants to flip a coin 10 times. The participants were told that they would receive a dollar for every heads they reported that they flipped, and on average, participants reported that they received 6.31 heads, well above the expected value, indicating that there was some cheating. Some participants were explicitly reminded not to cheat before they started flipping, and the average number of heads they reported was 6.22 heads, which was lower than the other participants. Yet, it suggests that cheating still occurred.

“What we’re talking about here is moving the needle,” said Miller, who is also the Project Director of the Honesty Project, which funds philosophy of honesty projects. “We’re not talking about eliminating the problem.”

As a professor himself, Miller utilizes such moral reminders to minimize cheating. Before his tests, he reads the honor code aloud with his students before tests so that the honor code remains fresh in student’s minds.

Likewise, English teacher Dr. GayMarie Vaughan started using the same moral reminders in her class last year, having her students write out the honor code before vocabulary quizzes. Vaughan believes that even if students hastily write “honor code” on their papers and quickly jump into the multiple choice section, it still helps students think about what it means to be a Marksman.

“We’re teaching boys how to live,” Vaughan said. “And if we want ethical leaders and good men, we have to keep those reminders at the front while they’re forming. Removing temptations is something that you do your whole life, and temptations are everywhere. We know the areas where we’re most tempted to stumble or to violate our own sense of ethics, and like I say in class, you have to build your own hedges around those places.”

Role models

For junior Andrew Xuan, the honor code is part of his everyday life. As part of the requirements to move up the ranks in the Civil Air Patrol (CAP), he was ordered to memorize, recite and live by the honor code. And now, as a flight commander in the Dallas Composite Squadron, he teaches others to do the same.

“You have the ability to inspire because you don’t know where cadets are coming from,” Xuan said. “They can be in terrible situations at home. For them, it could be an escape from home, and what you do there can literally change their lives. Taking that obligation seriously is just one of the things that we always keep in mind.”

When Xuan first joined CAP, he saw this obligation firsthand from his first sergeant. Since CAP is cadet-run, his first sergeant and those in other leadership positions are in the same age group as him and others they lead or have led, serving as role models everyday. Xuan’s first sergeant showed him what a leader can do to motivate a group of people. Even just by maintaining a forceful and energetic demeanor, Xuan saw the squadron’s demeanor change.

One quasi-experiment yielded near identical results, showing that having role models amongst one’s peers, like in CAP or at school, can be much more effective than having historical role models. The experiment split 107 eighth graders into two different Moral Education classes that met for three hours a week. In one of the classes, a teacher led the students to evaluate and praise some of the exemplary behaviors, like charity work, of someone close to them, with a focus on a few virtues per class. In the other class, students, instead, evaluated and praised the exemplary behaviors of historical figures.

Afterwards, researchers found that those who had role models amongst their peers were far more likely to engage in volunteer work as opposed to those who had historical role models. Furthermore, in the group that had role models amongst their peers, there was an uptick in the student’s engagement in voluntary service before and after the Moral Education class.

Yet, to truly have a role model that spurs action, Miller believes that admiration is not enough.

“We admire all kinds of things that don’t change our lives,” Miller said. “ Admiration, though, leads to inspiration, which psychologists call elevation. That means emotionally wanting to become more like the other person with respect to what I admire about them. This emotional response can, in turn, lead to better behavior.”

To get students to have better behavior and embrace the school’s values, Miller believes that the most important thing is for teachers and administrators to embody the values themselves.

“Before you do anything formal, before you do any classroom instruction, it better be the case that these values are being exhibited and demonstrated in the lives of the leaders of the school so that they can become role models of the very things that they’re trying to impart to the students,” Miller said. “It’s more powerful to see it lived out in someone you respect than it is maybe to have a discussion group, a computer game, or a worksheet.”

And even in the most intense environments, seeing role models in action leads to people following in their lead. Considered one of the toughest physical training regiments in the world, Basic Underwater Demolition / SEALs Training is a year-long course designed to break, rebuild, and harden men into one of the most elite fighting forces in the world. Every year, of the near 1,000 aspiring Navy SEALS, all of whom are top tier athletes, only about 250 men graduate with a trident.

But though it may seem like the people who pass the course do it themselves — out of sheer passion and pure will — that premonition couldn’t be further from the truth. In reality, their success, too, depends on the people around them.

It’s the inherent swooping feeling when a fellow soldier down is let down that really carries them through training.

Drill sergeants don’t instill discipline. The brothers do that.

“Peer mentors are some of the most effective mentors, because they’re your friends. Those are the people who can really motivate you to behave a certain way,” a Navy SEAL, who spoke under anonymity, said.

According to him, the idea of a brother in the military is the same as a fellow student. Just like how soldiers in the military withstand challenges together, students struggle together and lift each other up.

As a plebe at the Naval Academy, Taylor saw this done every single day. In the pool, he saw the upperclassmen never take a set off. Out of the pool, he saw midshipmen that would offer free tutoring hours once or twice a week to help other midshipmen get through the school academically. And through his leadership classes, he learned about the historical figures like Admiral James Stockdale, who had once been at the Naval Academy.

“It’s a leadership laboratory, and you either sink or swim,” Taylor said. “You either get on the train — adhering to the traditions, working hard, learning how to lead — or you don’t.”

Punishment

And for those who don’t adhere to the traditions, the consequences can be severe. After two years at the academy, all midshipmen commit to two more years at the academy and five years of service to pay for their education. If expelled from the academy, The Baltimore Sun estimates that the student would be on the hook for around $186,000 to pay for the cost of their education.

“There were definitely times where I’ve walked into a test and knew that I could have cheated, but I just punted on those tests and did poorly instead,” Taylor said. “There are always ways to recover from doing poorly on a test, like showing the teacher that you actually care and doing better on the next one.”

At the Naval Academy, everyone knows when someone receives an honor offense. If a midshipman is put on restriction as a result of this honor offense, they’re forced to walk tours at 5 a.m., marching around in a square with a rifle for an hour.

“As you get more senior at the Naval Academy, you realize that the consequences for doing something stupid could result in expulsion, and it could be a big deal,” Taylor said. “Versus, maybe I can survive even if I don’t do that well in this one task.”

Taylor has sat on the Naval Academy’s honor boards before, where a group of midshipmen decide whether their peers have cheated or not.

“It’s almost like a mock trial,” Taylor said. “You listen to the kid plead his case, and you gather facts about the incident. The consequences are real.”

Taylor, though, feels this degree of punishment, although effective at the Naval Academy, could never work here. Miller agrees, for the school aims to foster a community that develops the virtue of honesty itself.

“In order to be an honest person, there’s more involved than not cheating, not lying, not stealing, and not taking part in these dishonest actions,” Miller said. “It also matters why you’re not doing them.”

Miller organizes the motivations to pick the higher road in two — virtuous and vicious motivations. Miller believes vicious motivation is self-centered, for someone with a vicious motivation only does the right thing to avoid punishment. Such motivation cannot be fostered in order to truly build the virtue of honesty.

Yet, Miller believes that curbing cheating is a good enough goal to aim for and punishment is an effective way to achieve it.

“Even if it doesn’t automatically get us to being honest, what you hope for, over time, is that people will come to see that there are other reasons for not cheating besides not getting punished,” Miller said. “And hopefully, over time, their motivations will evolve.”

Commitment

To get students to follow the ideals of the school, Miller believes there must be ways to commit to those same ideals.

“You have to make sure that there are actual ways to act them out,” Miller said. “Things like volunteering opportunities, where you’re actually helping people and not just talking about it or sitting around and working on a worksheet, but you’re actually putting the idea into practice. It also can’t be one-off, but it’s got to be done over and over again to slowly develop the virtues and make it habitual.”

In CAP, Xuan feels a lot of the reason why cadets follow their leaders, adhere to the honor code and put its core values into action is because they want to be there and are committed to their unit.

“This is an example of why parents, in my opinion, shouldn’t really force their children into activities,” Xuan said. “Because in this case, if they’re not motivated, they’re not going to well. There’s a lot of discipline and effort involved in getting it right. I’ve seen a lot of cadets who show up for a few meetings and just disappear. There aren’t very many who actually stay.”

In the military, this dedication to discipline is instilled through basic training itself.

From the moment they enter their respective academies, recruits are already constantly reminded of the expectations they’re held to. From shaving heads to 4:30 a.m. wake up calls, bootcamp is inherently designed to instill discipline and drive in soldiers.

For the SEALs, there isn’t a no-man-left-behind attitude. The training is a test in and of itself — failing means quitting the program, and passing means joining and serving an elite fighting force. Inherent motivation is a requirement, and those who don’t have what is necessary collapse.

And with the BUD/S program being as elite as it is, to be a SEAL, motivation is all that matters.

“Most of the guys who apply are super fit — a buddy of mine was an Olympic trials swimmer, and another was globally ranked for running. But in the end, nothing matters more than mental toughness,” an anonymous SEAL said.

The drive comes from something within a person – something that originates and starts with their inner self. To truly carry out a task at hand means truly wanting to accomplish one’s goals.

“My desire carried me through my training,” the SEAL said. “If I quit, I would just be in the fleet on a ship doing another job, which is something I didn’t want to do. There were times where the greatest thing in the world was a warm shower. But everytime, being temporarily relieved of the pain was always beat by my passion and desire to become a SEAL.”

For many SEALs, the motivation is best characterized and personified as a “Why.”

“You need a very crystal clear ‘why,’” a Navy SEAL said. “If that’s not very clear, then you should go do something else. You should do the thing that you want to do, that’s going to be good for you in the long term. And in order for you to do that, you have to know what it is.”

And for the SEAL, after figuring out a personal “why”, the rest of the work is purely based on focusing on it, and slowly getting through it all, one step at a time.

Ultimately, for him, in a world where failure is always looming, sometimes it’s better to take it slowly, and with discipline.

“It’s not about taking cold showers or prepping yourself by being wet and cold all the time,” the SEAL said. “It’s about being mentally tough, not cheating yourself, and the desire to get through it all.”