Two days before spring break, the atmosphere at school was unsurprisingly chaotic. A naive cheerfulness filled the air as students joked with each other and talked about their plans.

News of DISD and other private schools canceling due to COVID-19 had spread across campus like wildfire. Then, 8th grader Alex Soliz had been one among many hoping school would cancel here as well.

He was also among those who thought it would all end in a week, at most a month — just a short extension of spring break, leaving more time to hang with friends and relax.

But it was far from that.

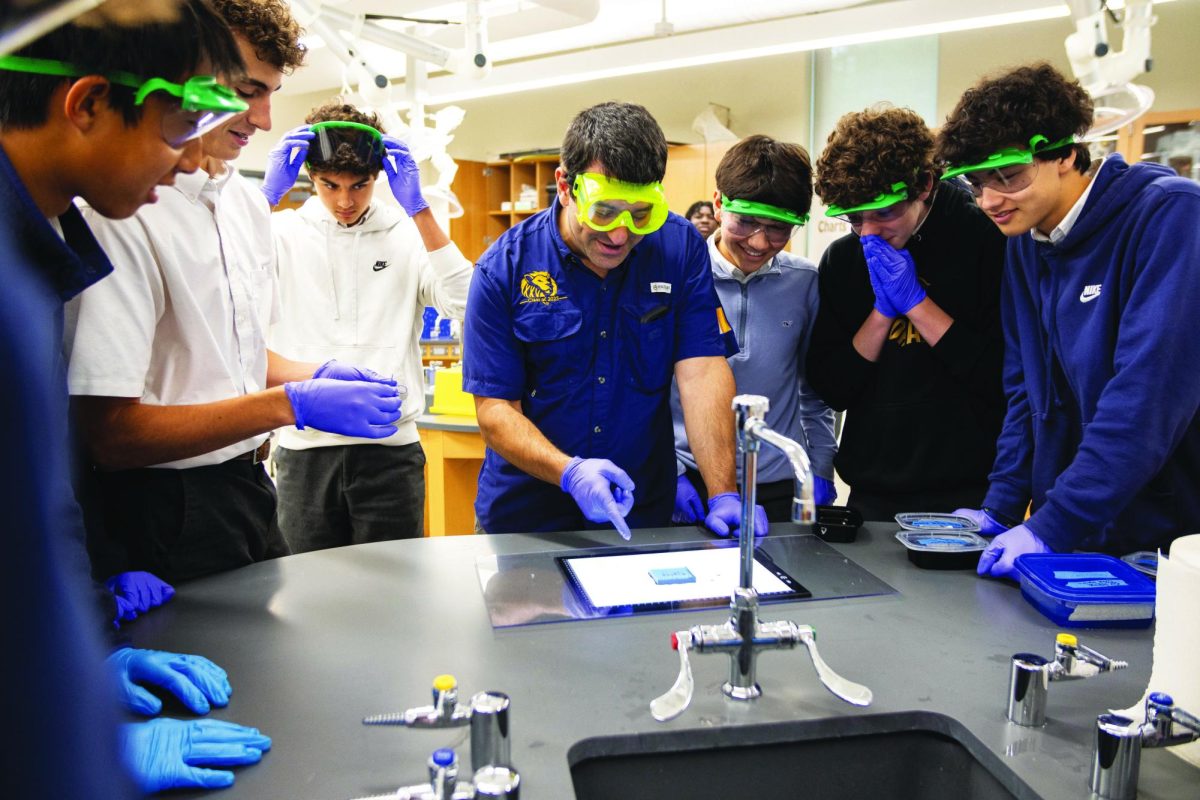

For the parents, a nine-to-five was replaced with work at home. For students, math problems on white boards were replaced with daily Zoom sessions. For kindergarteners, days spent swinging from the playground’s monkey bars were replaced with tablets connected to calls.

Parents had to worry about their children’s every meal and accommodate their time at home. Students were starved of class time and academic development. The youngest kids were losing crucial time to develop social skills.

Soliz was one among many who wished they had those years back.

“All I did was play video games,” Soliz said. “I wasn’t really allowed to go see my friends except for one of my friends who lived really close to me. It really did suck.”

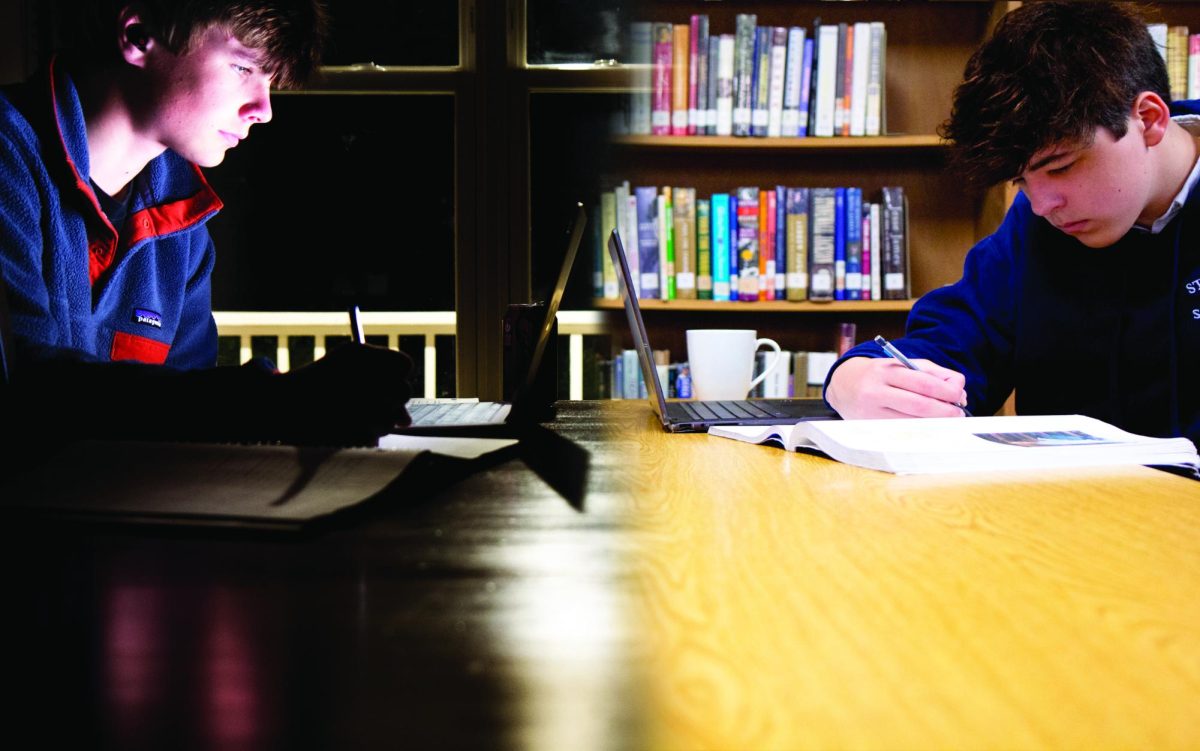

In addition to the apparent social connectivity issues, Soliz believed the pandemic softened the school experience for students.

“On Zoom, you just have to wear your school shirt,” Soliz said. “Nobody’s paying attention to if you’re wearing pants or not. Now, I get to school at eight o’clock every morning, even if I have first period free. Online, I remember I was waking up at like 8:20 to go to my 8:30 class. I found myself getting really lazy and not caring as much because it didn’t feel real.”

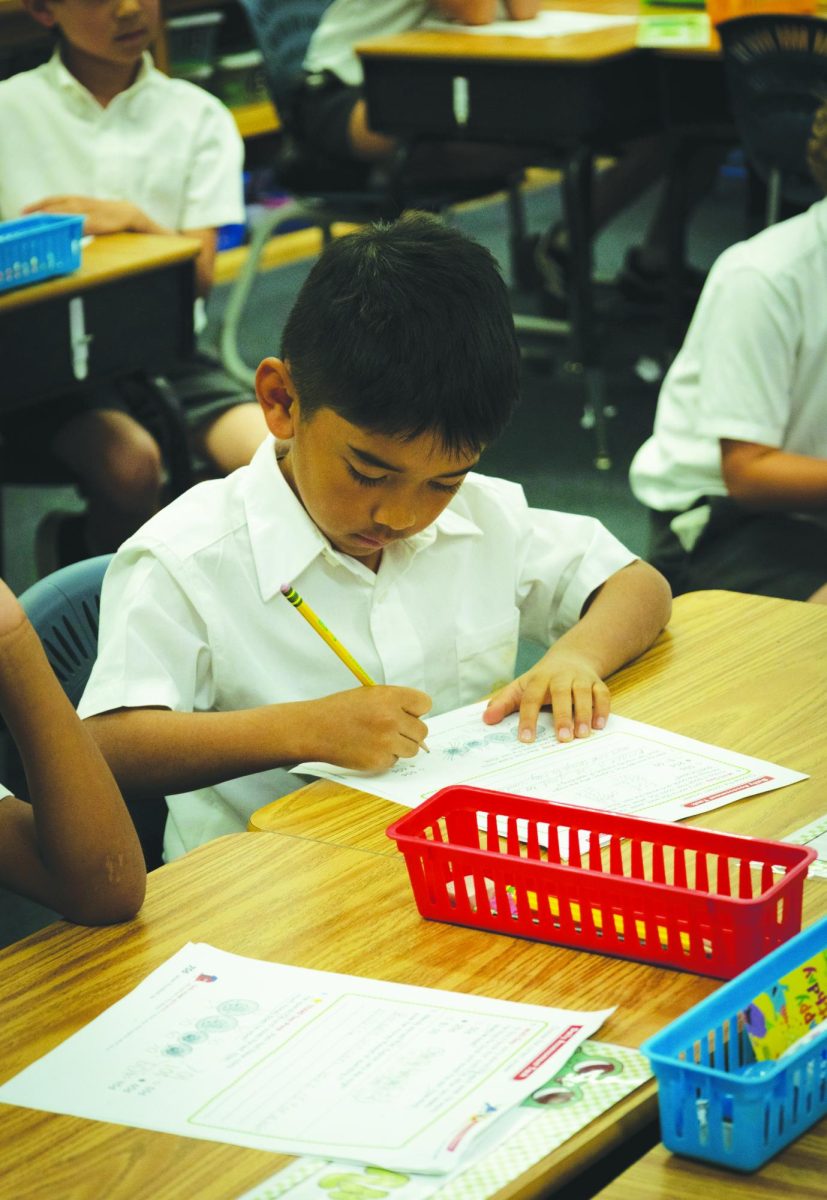

While older kids like Soliz didn’t get to see their friends, and college-ready seniors didn’t get to enjoy their last monumental year of high school, younger kids suffered the worst consequences due to the lack of social interaction at such a young and developmentary age.

“I think it affects the younger kids the most, because being with other students in preschool or when you’re really young is a huge social point in your life.” Soliz said.

This absence of human interaction left an irreversible impact on some kids, as crucial social growth occurs in the brain during this time.

“I was talking to one of my friends who has a first grader buddy, and he said his kindergarten year and the year before that were online, so he’s really shy now and doesn’t really interact with his friends that much,” Soliz said. “So I think it’s the worst for them.”

For young kids, where difficult and rigorous studies isn’t the main focus but developing social skills is, quarantining significantly hindered social proficiencies.

“There might have been a wild situation in the kindergarten phase,” Upper School Counselor Dr. Mary Bonsu said. “(The younger kids) may have missed out on the areas of their brain that develop from just being able to read social cues visual cues, and practice things like sharing and being in spaces with other kids their age.”

Akin to these children, maturing teens also faced similar challenges socially through the pandemic.

“For kids around age 13, their brains start to rewire itself and advance in their need for social rewards from peers,” Bonsu said. “Social relationships become very important. The brain becomes activated by warmth and pure acceptance.”

As young kids faced an increase in developmental delays, learning disabilities and more, other psychological repercussions, such as anxiety and depression have increased since the pandemic.

“There have been terms like collective trauma that have been thrown around,” Bonsu said. “Many of us will have an emotional reaction to just even seeing the mask, right?”

Although social-distancing forced students to cut physical contact, Bonsu highlights certain ways in which it alternatively had a positive impact.

“I definitely think COVID-19 allowed us to connect in new ways,” Bonsu said. “It has had a positive outcome on adults, since it’s allowed more flexibility for adults to be able to work from home and spend a little bit more time with their children.”

According to a study by the National Center for Biotechnological Information, children who spend significant time with their parental figures and friends have a mental well-being that is healthier than kids who do not. The negative effects following the latter reflect on the lack of connection during the pandemic. To combat this, kids turned to new ways of socializing.

“Technology tried to account for that lost social time, and it changed the way in which kids interacted,” Bonsu said. “Connections were made through online means. There was more online gaming, there was more texting and more socializing through social media.”

In the polarizing wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, fundamental changes within the development of kids seemingly alienate this extraordinary generation in ways previously unseen and unpredictable. The rapid innovation of technology and sociology reshaped society, sparking world-wide debates among experts.

“The pandemic unfortunately resulted in a lot of loss,” Bonsu said. “However, I think it just made us value life a little bit more, and I think that goes across all ages.”

COVID-19: four years later

It’s clear that the pandemic left its legacy through increased learning issues and loss of countless lives. However, the social reprecussions are often overlooked – isolation has brought a surge of anxiety and other disorders.

March 8, 2024

Categories: