It was his second choice.

Senior Harry Wang had done orchestra in eighth grade. He’d been pretty good at violin, but to be honest, he didn’t really enjoy orchestra that much.

So he picked up debate as a second choice. He wasn’t particularly serious at all. He just showed up at tournaments occasionally with friends.

But after seven weeks of debate camp the summer before his junior year, Wang realized that he actually wanted to be serious about debate.

And partnering up with senior Liam Seaward, they practiced and tried to do well but ended up only with a “decent year”.

Back again to seven weeks of debate camp, they aimed for top 20 in the nation.

But their aspirations never came true. They didn’t do great at the first few tournaments and lost their chance to continue debating at the next bigger tournaments because of their poor results.

Maybe it was just bad luck. Maybe we should’ve prepared more. Maybe I should’ve been serious about this a lot earlier.

He felt that it all stemmed from those first few years of debate — the lack of care and commitment. Regret.

It’s not his first time feeling like this. Sometimes he wishes he had tried harder in school. Sometimes he wishes he had learned to drive earlier.

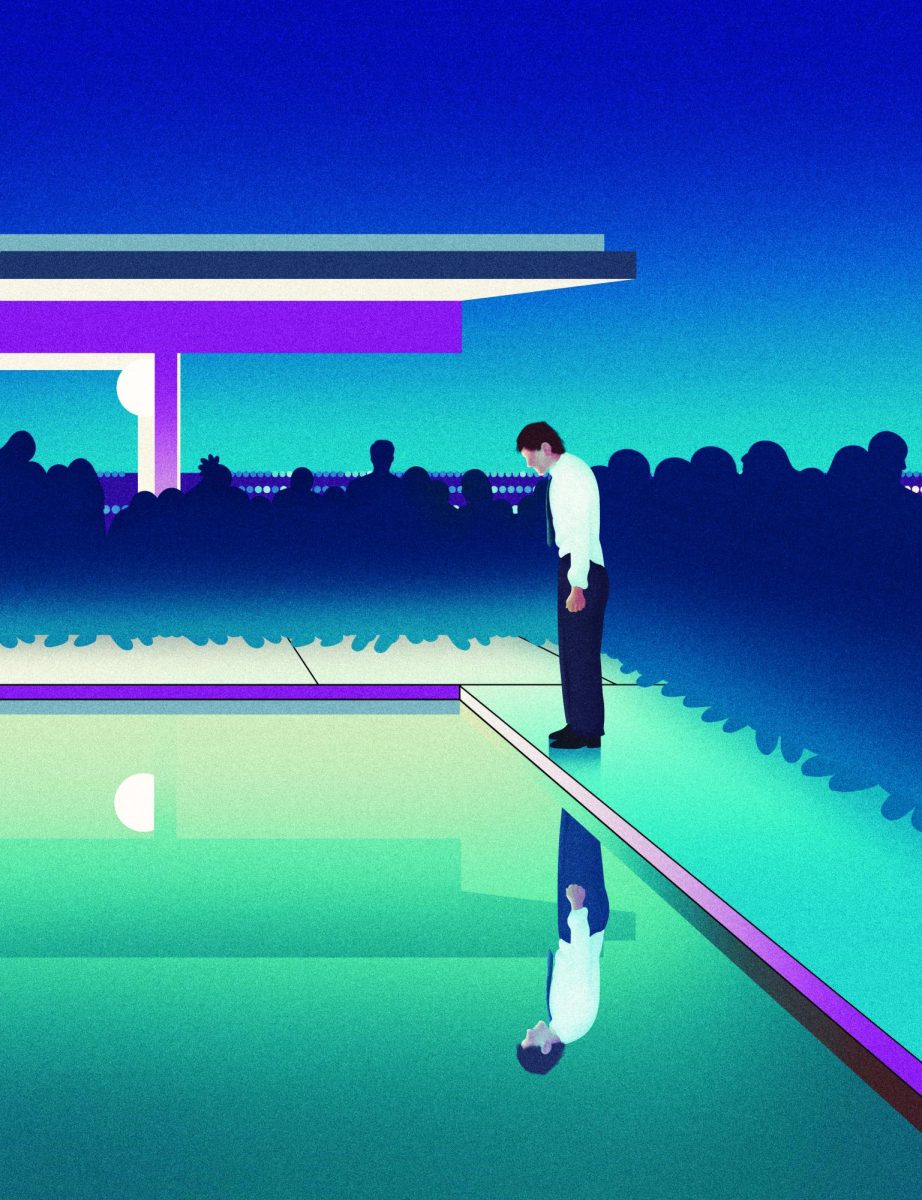

Regret is something everyone has felt. Breaking a promise. Not working hard enough. Missing an opportunity.

But it’s how we deal with it that sets us apart.

And Wang wants to change it. Get rid of it. He wants to redeem himself in college. Work really hard and see what becomes of his first year of collegiate debating.

But many don’t want change it. Or can’t change it. Don’t want to deal with it. Or can’t deal with it. Don’t learn from it. Or can’t learn from it.

Sometimes, many get stuck with regret.

Regretting. Again and again.

Forever.

For Sally & Edward Genecov Master Teacher Amy Pool, much of her supposed regret comes in the form of life-changing and career-defining decisions.

After acquiring her Bachelor’s degree in Mathematics from Portland State University, Pool was met with a choice, a fork in the road. On the one hand: to stay in school, to chase her Master’s degree and a higher education. But on the other hand: an opportunity to grow, to expand her zone of influence, and to start her career.

It was one or the other. There was no in between.

In the end, Pool chose her education. For her, there was nothing more important than pursuing her passion and her love for learning. And within the next four years, she completed her degree, completing her dreams for higher education.

But yet again, she was met with the same crossroads: a memory of that past. Now, she was given the opportunity to chase another level, and another dream. Once again the two hands were presented to her: to venture out to seek a PhD, or to begin a new chapter, where her life would inevitably change.

Again, it was one or the other. There was no in between.

And nearly 25 years later, it’s clear that Pool’s decision panned out well.

But even despite the success her decisions have yielded, there’s still a fraction of Pool who would’ve pursued her next degree: a fraction fueled by her immense curiosity and love for learning.

“I love being a student,” Pool said. “I would have loved to have done my PhD.”

But had Pool ventured out to secure her PhD, she would’ve found herself in an entirely different field. Had she sought that level of higher education, her environment, surroundings, and area of expertise would have been completely different. Had she done virtually anything differently, she would’ve never ended up teaching the boys of 10600 Preston Road.

“I have a hard time seeing these things as regrets because those decisions ultimately put me on a path that I never would have experienced, and that I would have hated to lose. There are plenty of things I don’t regret because I look at the consequence, and admire the positive outcomes of that consequence.

But instead of regretting and lingering on some of the biggest decisions of her life, Pool instead finds her that her most regretful actions in life have come from the small things in life.

In college, Pool, like any other college student, was friends with the people she took the most classes with. Like any other college student, she had study groups, where she bonded with her classmates through late night problem sets and study sessions. Like any other college student, her experience was mostly normal.

But unlike any other college student, one of her closest friends had told her that he was going to commit suicide.

Starting out as acquaintances who had found each other through their shared business major, they transformed into friends who had underwent some of life’s toughest challenges together. When she she struggled, he helped her. When he struggled, she made it her mission to get him through it.

And after a particularly rough patch, where he and his girlfriend had went through a particularly nasty split, Pool had thought that it was going to be much of the same. They had gone through this before: this time was just another, albeit obviously serious instance. Her strategy? Get him committed into helping her do things, so that he always had a purpose.

But then came the thoughts of suicide.

“At one point, he had told me that he was gonna kill himself over [his situation].”

What are you supposed to do, when someone approaches to you with that on their mind?

For Pool, her thought process was much of the same: to keep requesting help in hopes that in the end, it would all be okay.

And it was okay. At the end of the year, Pool had invited her friend to a dinner on New Year’s Eve. At the time, Pool had worked the graveyard shift, so the plans served as a break. It was a way to spend more time together, and to relax.

Around halfway through December was doing exactly that: relaxing after a long day classes preceded by a grueling graveyard shift. But as she slept, she was suddenly woken by a call.

A call? For me?

People who knew her well knew of her exhausted schedule, so calling in the middle of the day seemed inopportune. But as she listened to the words that were being spoken, her nightmares turned instantly into reality.

It was her economics teacher, asking her if the name he saw on TV was the same one he knew. A high speed chase, where the driver had shot himself. A suicide.

“And that’s how I found out that he’d actually done what he said he was going to do.”

Up until the event actually happened, Pool was confident in her ability to push through. After all, she had done it multiple times before – what was the difference this time? But the instant it happened, it was as if all other questions and routines ceased to exist.

There was nothing to change, nothing that could’ve been done to prevent this exact set of circumstances. What’s done was done, and no matter how much she wanted to, she could never change the past.

But after reminiscing after all these years, there’s still remains one thing that she wish she could’ve. But contrary to any sort of conventional wisdom, she doesn’t regret the big things, rather, she regrets the smaller things. Instead of focusing on massive actions which she could have done to help prevent his death, Pool is, on the contrary, plagued by her inaction in the most common of situations. Like not having made the extra effort to say hello.

And more than 20 years later, these regrets still dominate Pool’s mind.

But from a purely educational and academic point of view, Pool’s regret from her situation is nothing new. According to Director of Marksman Wellness Gabby Reed, the little things are often just as easy to regret than big mistakes.

“I think it’s easy to get hung up on the little things, because the little things are things that we feel like we can control,” Reed said.

Reed has seen experiences very similar to Pool’s unfold before her eyes. Most recently, Reed witnessed the implications of the death of her husband’s best friend on her husband.

On any other day, he would’ve picked up the phone. On any other day, he could’ve called him back. On any other day, he would’ve called him back.

But on this day, he decided not to. And so the phone rang, and it rang, and it rang.

Oh, I’m busy. Oh, I’ll call him back.

But some time after that, and without a call back, his friend collapsed, due to a sudden and terrible heart attack. And even though they had shared a myriad of hours together on that very same phone call, it was this last call: this insignificant missed conversation over the phone that Reed’s husband would regret.

“It’s not that often that we have a chance to jump in front of train to save a baby,” Reed said. “But everyday, we make little choices that have massive ripple effects on our lives.

But from a purely educational and academic point of view, Pool’s regret from her situation is nothing new. According to Director of Marksman Wellness Gabby Reed, the little things are often just as easy to regret than big mistakes.

“I think it’s easy to get hung up on the little things, because the little things are things that we feel like we can control,” Reed said.

Reed has seen experiences very similar to Pool’s unfold before her eyes. Most recently, Reed witnessed the implications of the death of her husband’s best friend on her husband.

On any other day, he would’ve picked up the phone. On any other day, he could’ve called him back. On any other day, he would’ve called him back.

But on this day, he decided not to. And so the phone rang, and it rang, and it rang.

Oh, I’m busy. Oh, I’ll call him back.

But some time after that, and without a call back, his friend collapsed, due to a sudden and terrible heart attack. And even though they had shared a myriad of hours together on that very same phone call, it was this last call: this insignificant missed conversation over the phone that Reed’s husband would regret.

“It’s not that often that we have a chance to jump in front of train to save a baby,” Reed said. “But everyday, we make little choices that have massive ripple effects on our lives.”

For senior John Zhao, one of those choices came in sixth-grade.

All the other band kids wanted to do percussion. And he did too.

But only ten could get it. Instead, he and the other disappointed sixth graders got their second choices. Zhao had picked the trumpet.

There’s only three keys. How difficult could it be?

And, oh, how difficult it was.

It was frustration beyond anything he’d ever felt. Considering he’d been playing piano since he was five, which had 85 more keys than this hunk of metal, it should’ve been easy.

There were so many things. Intonation. Embouchure. Transposition.

But he stuck to it and practiced. A lot.

“Maybe I could’ve done something better with my time,” Zhao said. “But this is all hindsight. There’s no way I could have known this way back, when I was deciding to play the trumpet, that it takes so much time.”

With that time, he could’ve done an extra science elective. Maybe done some computer science ahead of college so he wouldn’t have to start all over with learning something new. But Zhao doesn’t dwell on it too much.

“When I decided to join band, I knew that I was going to have to sacrifice some time for it,” Zhao said. “I just used the knowledge that I had at that time to make the best decision on what to invest my time in. And if that ends up not being the best investment, then what could I have done?”

Latin instructor Dr. Andre Stipanovic once dreamt of playing on the big stage. Of making it big in the music industry.

And going into college, he was debating whether he wanted to go full time into music — with his guitar skills he’d picked up in high school — or just stay in school.

But he chose, ultimately, to study computer science at the College of Engineering at Rutgers. He knew it was his opportunity to get an education, and he still had the chance to play in groups at college too.

His classes were interesting enough — it just wasn’t his passion. It wasn’t what he wanted to do — except, he really didn’t know what he wanted to do. His father had told him for years that the College of Engineering was the way to go, and after Stipanovic had gotten out of the army, he was told that computer science was the future.

Before then, Stipanovic had never taken a Latin class. He’d taken French and German in high school and hadn’t had room to fit a Latin course in.

It was only in college that he had the opportunity to try out other subjects, finding his love for Latin in the process.

Sometimes — like in his graduate work — he wishes that he’d started Latin sooner. Guitar too. But, like Zhao, he doesn’t like to dwell on it.

“I always remind myself in the morning of memento mori — remember that you are going to die,” Stipanovic said. “Every day you’re alive, it’s one more thing to be grateful for and one less thing to regret.”

Stipanovic still has regrets, though. And to him, it’s fine. It spurs growth — it keeps him vigilant about his actions. It’s made him make sure to stand up for his friends and try to be closer with his brother. Not knowing his passions for Latin and guitar from the start has allowed him to meet all sorts of different people from his varied experiences.

And ultimately, he feels it’s necessary.

“You can see it in literature,” Stipanovic said. “Literature is just a record of human experience. Even if it’s fictional, it’s still based on what people actually do. Show me one really good piece of literature that doesn’t have regret in it. It’s all there. It’s in Dante. It’s in the Aeneid. It’s in Homer. It’s everywhere.”

Reed defines regret as that state of looking back in hindsight on something, and wishing that you could have done differently.

“[Regret] often occurs when you imagine that alternative outcome that you wish had happened: one where you maybe made a different choice or decision,” Reed said.

But though the feeling is essentially universal across humans around the globe, different cultures have different approaches of interpreting and reacting to regret. In a country where individuality and perfection is strived for, like in the United States, regret runs rampant. On the other hand, with communities that are more collectivistic, regret is less common.

“These cultures that value community more, they’re people who see themselves more as like, part of a bigger group, and they take less of the blame on themselves,” Reed said. “In many Hispanic cultures, for example, they have more faith-based approaches. So if something doesn’t go their way, or if something doesn’t go right, they sort of go, ‘Well, God willed it to happen like this.’”

According to Reed, one of the best ways of dealing with regret is to simply learn from it – to harness that which makes one hurt, and apply it to different facets of his or her life.

“[Regret] was rated highest on a list of negative emotions in terms of fulfilling some pretty positive functions,” Reed said. “It can help us make sense of the world, and it can help us avoid future negative behaviors.”

The true dangers of regret come from complacency. Though it is beneficial to think back upon the past and methods to improvement, dwelling in the past and focusing on a past mistake is dangerous.

“When we get stuck in regret, all we can think about and ruminate about is how much better life could be if a difference choice was made,” Reed said. “That can lead to depression, it can mess with our immune system, and it can lead to anxiety.”

Like in the cases with Pool and Reed’s husband, one of the most common forms of regret comes in the form of not having interacted enough with a loved one. It is this inaction that can eat away at people, and propel them into darkness. But with a couple minor changes, these deeply harmful experiences can be turned into teach valuable lessons.

That regret from death implores us to care more deeply about the people currently around us. It forces to us to love harder. It forces us to hug a little tighter. It forces us to care more.

“It’s regret avoidance,” Reed said. “In the end, you’ll be able to look at yourself and go, ‘I did what I could have done and more.”