For those of us in a tucked-in oxford shirt, grey shorts and — can’t forget — a belt, many are fortunate enough to look forward to a set of wheels after finally passing that driver’s test.

But driving is not necessarily the norm in many parts of the world, or even the United States. A distinct hallmark of various countries in Europe and Asia, and even in cities like New York and Chicago, is a well-developed and accessible public transportation system.

And when it was announced in February that Arlington’s AT&T Stadium, despite hosting nine other matches, had not landed the coveted bid for the World Cup Final, which will instead be hosted at MetLife Stadium in East Rutherford, New Jersey, many have begun pry at the backbone of Dallas-Fort Worth’s own public transportation system as a possible reason for the decision.

Additionally, with spring break around the corner — a time for Marksmen relatives from other cities and countries to come visit Dallas — many may find themselves shocked at the sheer number of cars and the difficulty of mass transit.

So in a metroplex where less than 5-percent of households were without a car as of 2018, has a city so intertwined with automotive freedom left those in need of safe and accessible public transportation behind?

***

Before junior Teddy Fleiss received his driver’s license, he took the Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART) bus home from school most days, which he saw as a viable alternative to waiting hours for his parents.

“My dad worked and my mom was always busy when school got out,” Fleiss said, “so I took the DART bus home. I used to live in Los Angeles, and all the schools there had buses to take kids to and from school, so my parents weren’t used to driving me. The bus was pretty convenient for me, because the stop is right outside the school, and there was never really anything to worry about; I never really felt unsafe or anything.”

Fleiss’ feeling of security may be a result of DART’s recent efforts to emphasize rider safety, according to DART Chief Communications Officer Jeamy Molina.

“Since our new CEO Nadine Lee came on board, she has worked to make sure that cleanliness, safety and reliability are in our DNA,” Molina said. “We’ve taken a lot of steps to make sure that we’re providing a safe ride, such as by increasing our police department staff — we’ve added 100 transit security officers to the system. We also recently added a program called DART Cares, a multidisciplinary response program in partnership with Parkland Hospital, where we have paired a DART police officer, a paramedic and a social worker from Parkland to help with the unhoused on our system.”

Molina also claims that DART is now more accessible than ever.

“I think there’s a lack of awareness for how easy it is to access our system,” Molina said. “We have the largest light rail system in the nation at 93 miles. We cover 13 cities across DFW. We’ve increased the capacity of our bus routes to allow for more options. We have the GoLink option now, which essentially helps you get that last mile to and from a station.”

However, former Dallas mayor Ron Kirk acknowledges that DART’s expansion has not always been without detours.

“I helped open DART’s first rail line as mayor in 1995,” Kirk said, “and from the get-go there were challenges. Some people opposed the rails because they were ‘ugly,’ and there was a sense that if you bring these trains into North Dallas, you bring along ‘undesirable people,’ and they’re going to flood the neighborhoods, so they killed a lot of the rail lines, and it wasn’t until they were built that people saw the success.”

To this day, DART suffers from a lack of state funding, according to Kirk.

“We still have very little money from the state,” Kirk said. “So DART’s expansion is largely self-funded by member cities or supported by funding from the US Department of Transportation.”

***

The question of whether DFW’s public transportation system had anything to do with the decision to place the World Cup finals in the New York area over AT&T Stadium has a simple answer, according to FC Dallas President and Chairman of the Dallas 2026 World Cup bid Dan Hunt ‘96, who helped bring nine tournament matches to the city for 2026.

“The perspective of Dallas’ public transportation system had zero impact on the bid,” Hunt said. “It really came down to the perception of New York being New York. But we let FIFA know what the reality of Dallas is — we aren’t just a big city in the United States anymore — Dallas is now a global city and this World Cup helps validate that.”

According to Hunt, DFW’s car-centric culture has even caused FIFA to rethink previous assumptions.

“FIFA has said to me that (DFW) presented as good of a traffic and transportation plan as they saw in any of the big cities in North America,” Hunt said. “We also are causing FIFA to rethink the revenue opportunities that exist between the driving and tailgating culture — the economics of it that brings parking, merchandising and food and beverage revenue. So what was perceived as a negative at the very beginning became a major plus for a lot of the stadiums in the North American bid that can park cars.”

But Kirk maintains that the city of Arlington was possibly held back by its mass transit system because of the city’s decision to pull out of the Dallas-Fort Worth public transportation plan.

“Arlington is the largest city in America with no money committed to public transportation,” Kirk said. “They don’t even have a bus system.”

***

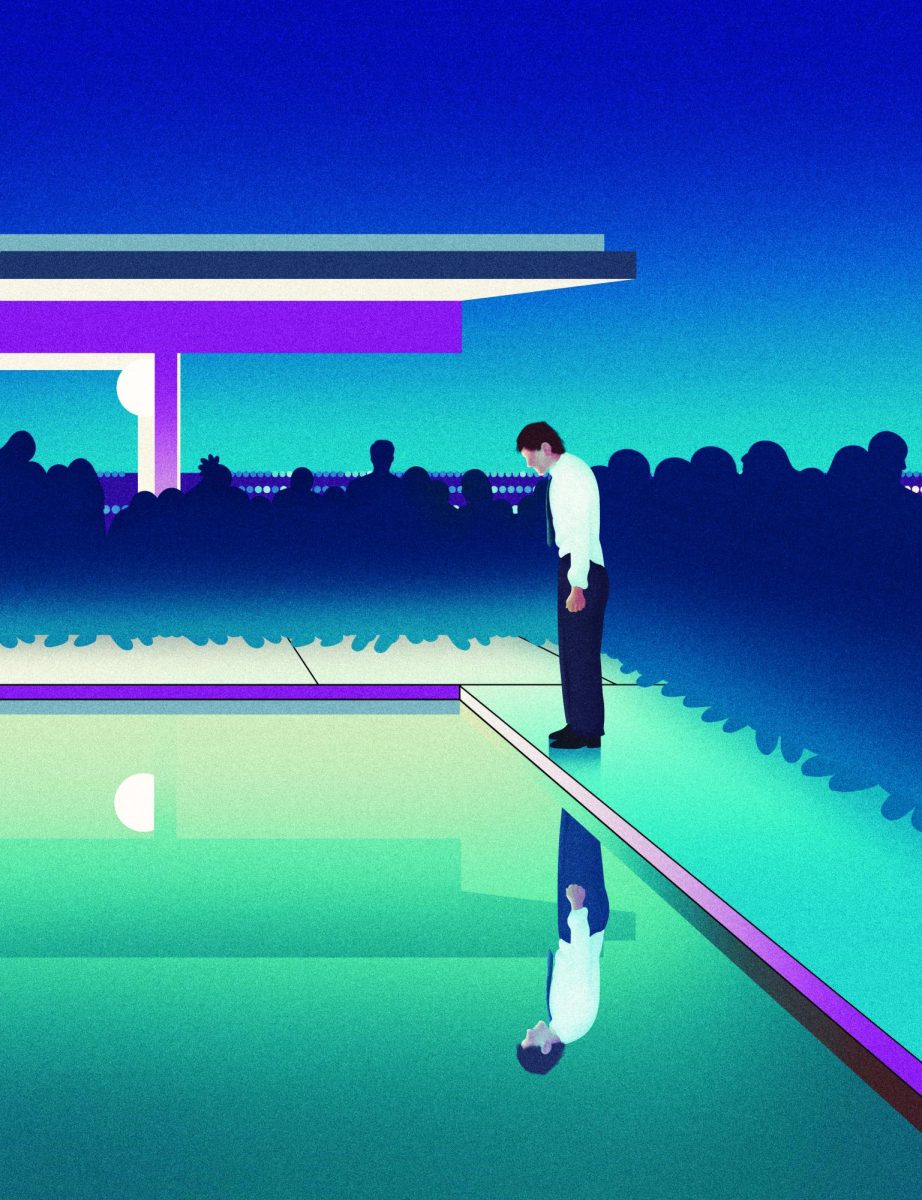

For Dean Itani ‘11, who currently lives in New York, a car-centric culture was exactly what he wanted respite from, and exactly what New York seems to combat.

“Having to walk 20 minutes or 30 minutes to the store, or even just my short 10-minute walk to work, promotes a more active lifestyle than driving your car,” Itani said. “And for the World Cup, where you’re talking about hundreds or thousands of Ubers that need to drop people off at the same location, (New York) can just send out more and more trains. Instead of coming every 10 minutes, trains will come every two or three minutes at those peak travel times so they’re able to move people around a lot faster.”

Itani believes not having to drive everywhere has a unique ability to make a city feel more accessible.

“Having to drive 30 minutes just to meet someone when I lived in Dallas quickly felt monotonous. But if you’re taking the subway and you’re walking, there’s something about it where it just feels like a shorter trip. It’s a little bit more engaging, and there’s more going on. For me, traveling in New York presents the chance to breathe; you can text, you can do whatever you want on the way there.”

But back home, one of DART’s original roadblocks — a public hesitancy to mesh with different people from around the metroplex — may be behind the wheel of a hesitancy to let go of car payments, save money on fuel and even cut down on environmental damage by taking public transportation, according to Kirk.

“Public transit has always had a little bit of a built-in classism to it,” Kirk said. “But I think a lot of it is generational. For example, my daughter who goes to college in New York rides the trains everywhere, so I think a lot of this opposition will dissolve as younger people go to school in cities that have transit.”

Ultimately, Kirk believes committing to expanding and improving public transportation in DFW is a necessity, regardless of whether everyone rides it or not.

“The reality is, to be a healthy, whole city, access to jobs and venues is critically important,” Kirk said. “And public transportation is the way we equalize that for those families that don’t have the luxury of being able to buy a car. It doesn’t bother me if people that don’t need it don’t use it, as long as they support the investments so that those people who do need it have access to it.”