Draw me Will Smith eating spaghetti in an oil painting in Van Gogh’s style, with high-quality 4K resolution.

What would normally take an accomplished artist days to paint is shortened to mere seconds. Thousands of brush strokes replaced with 1 clicks on the keyboard, then the enter key. In an instant, a 4K resolution image of Will Smith eating spaghetti renders on the computer screen.

This begs the question: can anyone be an artist? Or are there specific requirements that must be adhered to?

As large corporations such as Google and Microsoft funnel billions of dollars into the fastest-developing field of Artificial Intelligence, this technology will only become more advanced, more sophisticated — more human.

Middle and Upper School art instructor Kate Wood has heard the rumors and speculations — that painting is dead.

She doesn’t know what’s going to happen in the future. In 20 years, would her job as both an artist and a teacher still be available? AI has shaken the art world, with millions of artists’ careers on the line.

But looking back into history, similar events have happened before. In the early 19th century, a new form of art was quickly rising in popularity: photography.

“When photography was invented, everyone was saying, ‘painting is dead,’ and of course, painting isn’t dead,” Wood said. “Ever since then, we’ve been on a rollercoaster in terms of the definition of art, seeing examples that completely break the constructs of what we think art can be.”

In her classes, Wood not only permits but also embraces the increasing use of AI, allowing students to generate images for inspiration.

“I have a student who has used a reference image that is AI-generated for every one of his paintings this year,” Wood said. “He’s using this technology to help render images to get something out of his head into something physical.”

In many ways, artists can utilize AI in their projects, pushing the boundaries of creativity.

“This comic book has images created by AI, but texts created by humans so it’s eligible for copyright protection. I think that’s a positive example that’s empowering; somebody could potentially self-publish a graphic novel and not need a degree.”

Wood believes that the advent of AI supplements mankind’s inherent desire to express themselves through art. Now, most people have the ability to express themselves artistically without having to take professional classes.

“Being a mother and teacher of young children, I was seeing, firsthand, this early development and this insatiable desire to draw and scribble and paint and mold with your hands,” Wood said. “There is this creative force that every single person can all tap into — everyone can be an artist.”

Although Wood is uncertain about her future in the art field, she’s not opposed to change. Rather, she’s optimistic and almost excited about this new step of the evolution of art.

“AI is the newest innovative technology that we have to respond to,” Wood said. “I think we’re gonna see artists push themselves and use this technology in a way to further their art and creativity.”

To better understand the true capacities of AI programs in the realm of academics, Gene and Alice Oltrogge Master Teaching Chair and Chinese instructor Janet Lin created a deepfake video of herself with surprisingly minimal effort.

Deepfakes, synthetically created videos with manipulated human facial expressions and body movements, are powerful AI tools with the potential for deceptive media.

“I decided to create a deepfake because my mom sent me a video saying that there was a lot of fake information online, and she showed me videos asking which one was real and which one wasn’t,” Lin said. “So, I made one to show her that I could do it without saying a single word. I also showed my students this because I want them to know that there’s a lot of fake news out there. You have to make your own judgment.”

As more companies such as ChatGPT and Midjourney continue training various AI models, AI may soon be ingrained into our daily lives.

“The AI era is coming,” Lin said. “We can’t stop it. We can’t say that we’re not going to use it because people are going to use it anyway. So, what we need to do is train students. It’s ethical if you do something on your own that isn’t copied from AI, and you can use AI as a way to give some ideas on how to do it. For example, you can use AI to practice your Chinese.”

No matter how AI develops, Lin believes there will always be a clear distinction between humans and AI — one thinks and the other imitates thinking.

“You have to know that you are smarter than AI,” Lin said. “You can use AI, but how you use it and how ethical it is is an issue, and we need to train students on that.”

Beyond the classroom, AI’s influence has also permated into the music industry. Organist and Choirmaster Glenn Stroh sees AI as a tool that musicians can use to aid them in artistic processes, such as music inspiration and composition.

However, there are still some concerns that people need to be wary about. Along with the gray area that questions original compositions, there are definite lines that should not be crossed.

“A lot of what I’ve heard people say is that if you’re not monetizing it or profiting from using another artist’s vocals to create an imitation of them, then it’s okay,” Stroh said. “But if you pass it off in a way that’s deceptive, which isn’t good, then that would be unethical.”

These lingering ethical worries have already stirred some controversy among singers and songwriters. Music has been released that was completely constructed by AI algorithms, mimicking famous artists. But apart from mainstream music, Stroh predicts that the incorporation of AI might endanger music job infrastructure.

“I think we’re going to see a lot of economic impact within the music industry because AI might create situations where certain employers or certain works are obsolete,” Stroh said. “This can be people writing a jingle or making background music when you’re shopping or waiting on hold. That can now be created by AI.”

And yet AI’s capabilities are steadily growing to be more advanced.

“We know that Beethoven wanted to write another symphony, and fragments of this composition existed,” Stroh said. “In the 1980s, a musicologist reconstructed it based on [Beethoven’s] compositional language. Now, AI has done the same. I think it’s fascinating to have this tool available, and we’re obviously on the edge of a new frontier.”

Similar to the substantial attention AI has garnered in music and art, its abilities have also affected the film industry — people have raised questions about the ethics of AI usage in cinema.

“The most practical stuff is related to audio work,” film studies instructor Mark Scheibmeir said. “They can take somebody’s voice and essentially recreate it. If a sound occurs somewhere in the middle of a person’s dialogue, they have software now that’s capable of replacing it.”

Besides being able to produce audio composition from an actor’s voice sample, deepfakes are also explored in production.

“They’re not widely used yet. But again, all these things are in their infancy right now,” Scheibmeir said. “We can scan actors and recreate their image pretty easily. A while back, somebody licensed the rights to recreate James Dean, a classic movie star from back in the day.”

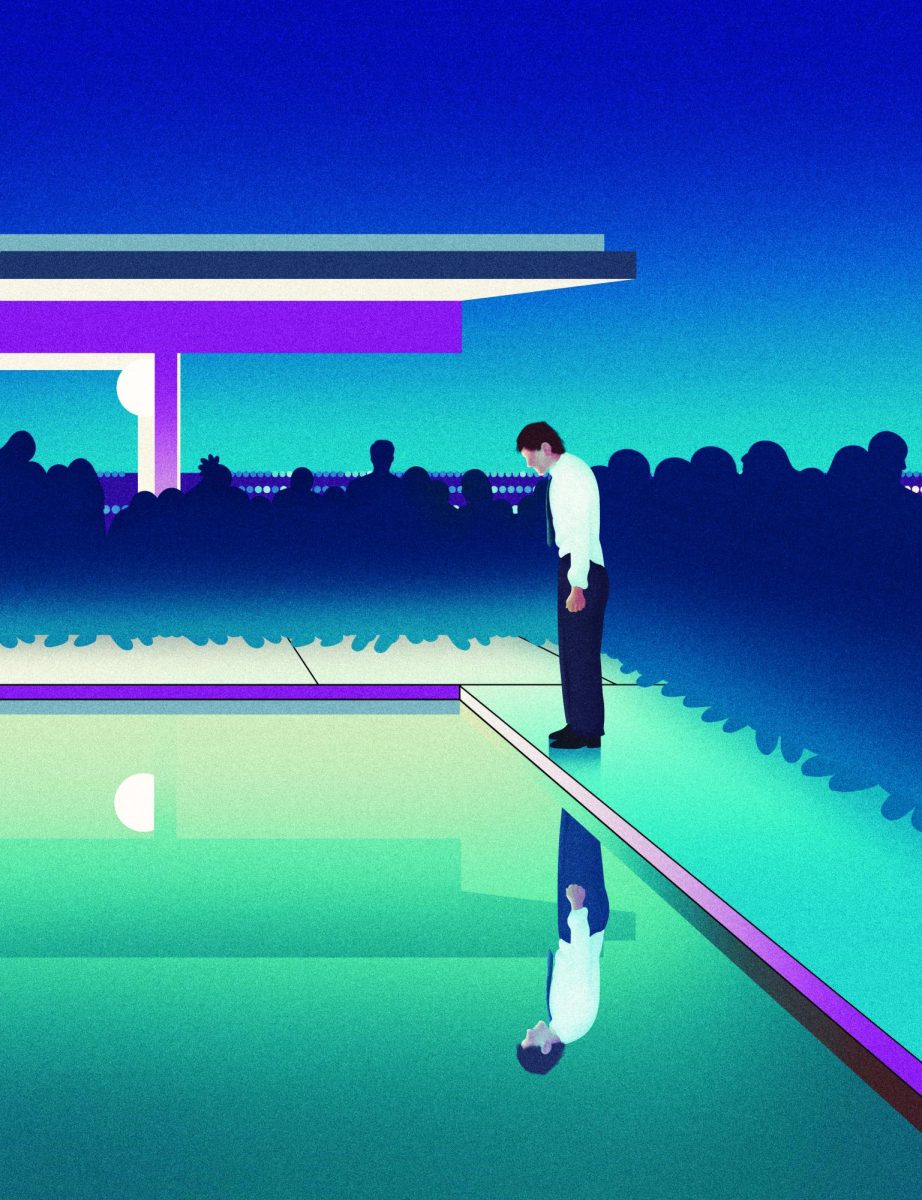

Dean, only starring in three movies before he died in 1955, was brought back to lead in the film “Back to Eden.” Although Dean’s career had been cut short, leaving fans wishing for more from him, his recent return through AI wasn’t received well.

“Everybody was like, ‘Oh, my gosh, we can’t do that. That’s so creepy,’” Scheibmeir said. “There’s questions of whether or not they can recreate this after the person’s gone. Who owns that? There is the human component of ‘Do I want to watch things that are created?’ It’s lab-grown in a way.”

Dean, along with the recreation of the late actor Peter Cushing in “Star Wars”, has created controversies about resurrecting dead actors, changing their legacy, and diminishing opportunities for living actors.

“I think the idea that we can own somebody’s likeness is a little off-putting,” Scheibmeir said. “There are religions in the world where capturing somebody’s likeness is actually against their religion, and when people took their first photographs, it was similar. “I think everybody needs to be on board. There can’t be anybody who says no.”

There are several parallels between AI and other advancements in the film industry. Initially, color and sound were received with skepticism in the early 1900s, and a similar reception happened with computer-generated imagery (CGI) in the late 1980s.

However, as those technologies became advanced, efficient and accessible, they eventually became a crucial part of many modern movies’ successes.

“We’re figuring out from a commerce standpoint, ‘what does the audience even want?’,” Scheibmeir said. “I imagine the conversation related to it will continue to evolve. If I put something in [AI] and it generated an image that you thought was cool, how much would you be willing to pay for it knowing that I spent five seconds?”

Like with CGI, Hollywood is grappling with whether audiences genuinely desire artificial elements in their entertainment.

“You take Tom Cruise’s nose and his eyes, and you give them Ryan Gosling’s mouth and you essentially create this sort of AI-generated human that has all these famous features,” Scheibmeir said “It’s nobody, right? It’s not a real person here. It’s not Tom Cruise. It’s not Ryan Gosling. As the audience, if we want to experience something artistic, do we feel like it needs to be human in order to get what we get from art?”