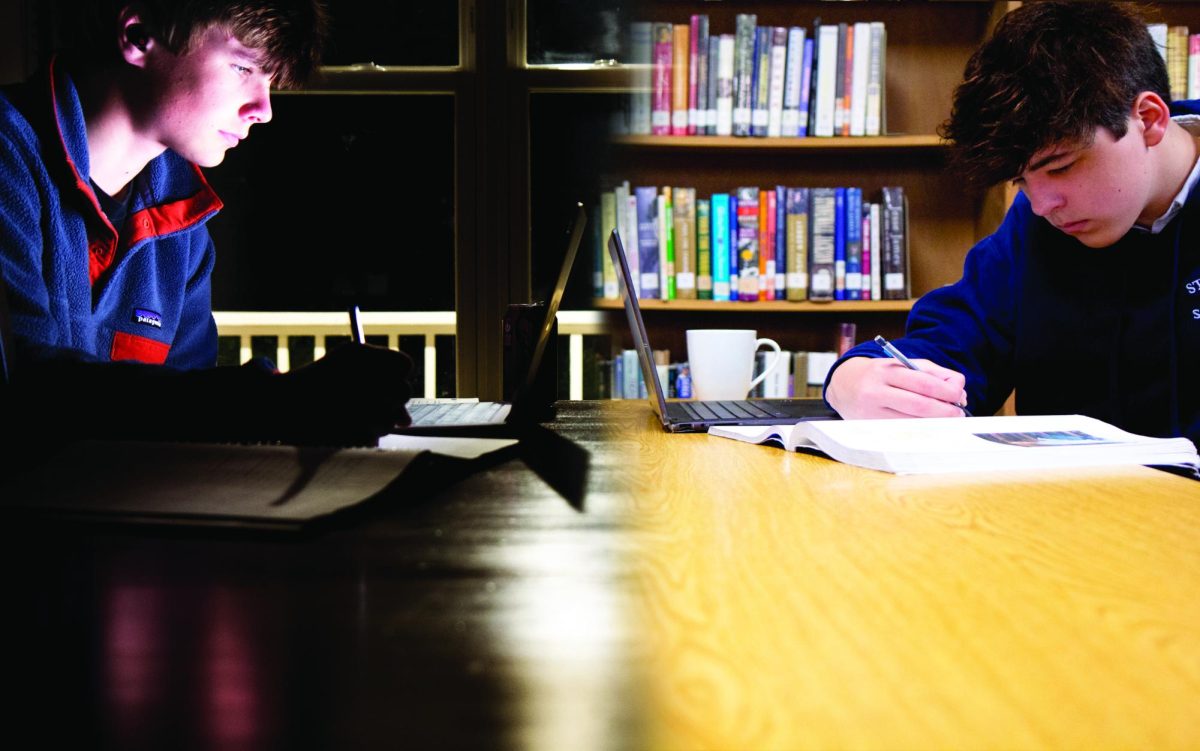

In a school where each class has around 15 students, everyone is familiar with each other.

But, in a company with thousands of colleagues, that personal connection seemingly disappears. Managing a small team for history class group projects and two-person English presentations about Song of Solomon becomes obsolete and impractical for working at a large corporation.

Besides the occasional Google Slides presentation and chemistry lab, the school rarely offers team-building opportunities in the classroom and instead emphasizes the importance of individual ability and work.

After several years of experience working with companies on Wall Street, English Department Chair Michael Morris believes in a combination of both group and individual activities.

“It’s good for the school to focus on preparing students for that kind of work,” Morris said. “I think we do it at a good level, but maybe that’s something that teachers could continue to prioritize.”

Before coming to the school, School Chaplain and Episcopal Priest Stephen Arbogast boasted a long career in finance, and similar to Morris, believes that there should be always a balance between collaborative and individual work.

Here, the ultimate goal is to prepare students for the next level of education. This places a heavy emphasis on the importance of individual work as students are being assessed by institutions for their own individual merits.

“It would, of course, be wonderful to teach more collaborative skills, but I think we can’t kid ourselves that the college admissions process limits the amount of flexibility we have toward teaching students,” Arbogast said. “We’re required as professionals to assess them and we’re required to assess them as individuals, not as members of teams.”

Another problem teachers face in instituting collaborative work is the difficulty of fairly evaluating the success of the group, contrary to the business world, where there are clear indicators of achievement.

“I think the biggest difference is that although there are a lot of subjective factors in business, at the end of the day, most things are quantified by dollars,” Arbogast said. “And so it’s much easier to assess the success of some activity than it is in determining whether someone is writing an essay better.”

Despite the contrasts between evaluating the success of groups in the professional world and the classroom, many similarities persist between the two.

“In English class for example, every time that you go home with a reading assignment, that’s like the independent work in finance,” Morris said. “Then you bring it back to the group, it’s not a team of four, it’s a team of 15, a class, and then the teacher is trying to coordinate the efforts of all of the students to contribute back to the to the group.”

While occasional collaboration occurs in the classroom, instructors still predominantly emphasize individual work for their students, which may be more similar to the professional world.

“There was group work, but there was also lots of individual work,” Morris said. “What the senior person would do is delegate different assignments to different members of the team, then you would go off and do your work and then bring it back to the team. Even though it’s different, a discussion versus a small team meeting, there are real parallels.”

Even outside the classroom, students have the opportunity to participate in student led organizations, allowing them to develop leadership skills through balancing teams.

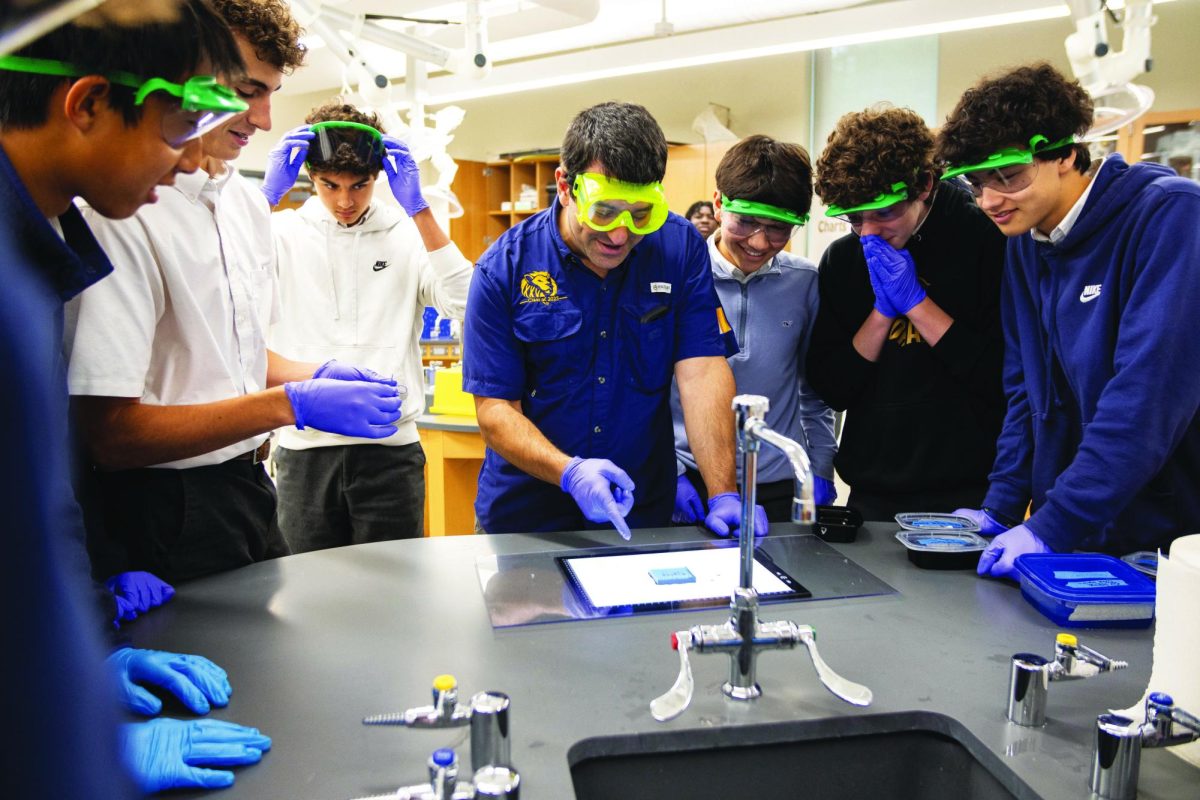

For sophomore Michael Yang, robotics has been a huge part of his high school experience. Along with others, Yang founded the first robotics team participating in First Tech Challenge, or FTC.

“We have nine people.” Yang said. “It was hard starting a new team this year because I had to work with the captains a lot to manage everyone. It’s hard to get everyone to communicate and work together efficiently.”

To build a high-level, competitive robot, Yang had to balance several aspects, from leading the team to ordering parts. Through the founding process, engineering and robotics teacher Stewart Mayer has helped Yang and the team.

“While Mr. Mayer doesn’t really do much of the actual leading, he teaches us how to manage, as he was the CEO of a company,” Yang said. “He always gives us a lot of tips on how we can help everyone to become a more efficient leader.”