The page blurs, his eyes an unfocused camera lens.

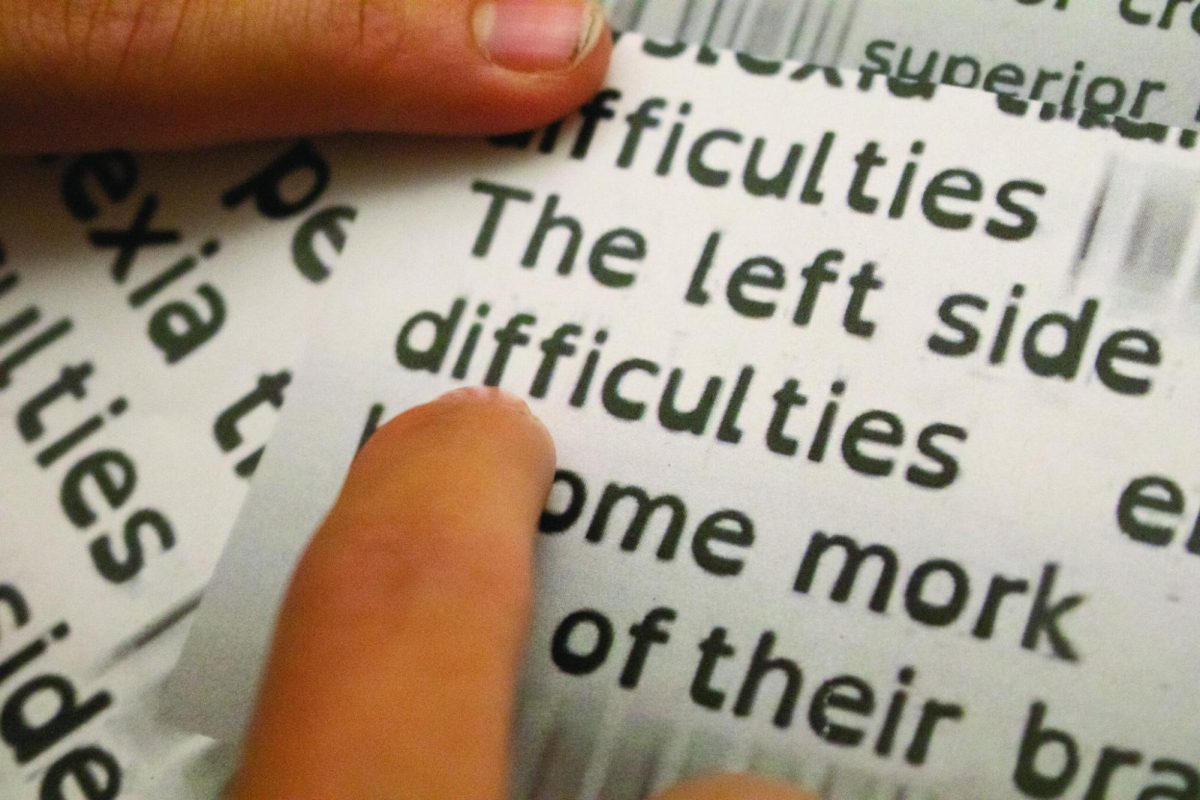

Running his finger along the sentence, the student carefully analyzes every individual letter.

Five minutes. One page of Wuthering Heights, this month’s AP English novel.

He goes to flip to the second of his twenty pages assigned for the night, then pauses halfway.

What did I just read again?

He can’t afford another abysmal reading quiz. So he brings his pointer finger to the first line and takes it from the top. He skims through it, trying to keep the jumbled mess of words from flying away this time.

No luck. So he re-reads.

Again. And again.

Junior Charles McCoin is the student that everyone goes to before quizzes and tests, asking him for his notes or for last-minute cramming. They only see the current Charles — the guy who understands every concept and consistently scores the highest. He hadn’t always been a straight-A student, though.

Diagnosed with dyslexia at 4-years-old, McCoin went through three years of specialized schooling just to get him to read faster. He was ranked the weakest reader out of his kindergarten classroom; he just couldn’t formulate the words on the page.

“I had to develop this technique when I was reading because I had read so slow,” McCoin said. “I’d skim over a sentence and just get the gist of it. I still do that now.”

Dyslexia is a phonological disorder that disrupts students’ abilities to translate between written text to spoken language. A proper diagnosis generally occurs early on when a child is first learning to read.

“Dyslexia is recognized in kindergarten, first grade and second grade, when students are starting developmentally,” Director of Academic Success Julie Pechersky said. “When people start to learn to read and they are not reading at the same rate as their same-age peers, a likely reason is dyslexia.”

After an early diagnosis, these students typically go through certain programs tailored to their dyslexia and reading capabilities. Specialists can then support the student in terms of his or her reading, writing and speaking skills.

“The best thing a dyslexic student can do is work with somebody who has been trained in dyslexia-based reading intervention,” Pechersky said.

At an academically rigorous school like St. Mark’s, students with dyslexia have to spend significantly more time reading and writing compared to their classmates.

“Dyslexia is a lot more than just letter reversal,” Pechersky said. “Dyslexic students aren’t able to naturally interpret and put together sounds the way a non-dyslexic brain would. They can read, but they’re not super efficient with it.”

At a young age, where everyone is still building their reading speed and comprehension, dyslexia can be hidden and ignored by fellow classmates. But some dyslexic students mature and leave their reading skills behind, widening the gap between them and other students.

Even as a junior, Hewes Lance ‘26 recognizes his underdeveloped skills in reading and dreads being put on the spot in English classes.

“Reading out loud gets kind of embarrassing sometimes,” Lance said. “It’s hard having to differentiate between some sounds like ‘U’ or ‘UE’ or ‘OU’.”

Dyslexia even impacts students’ abilities to understand others and communicate over the phone. With new acronyms being formed every day, it’s easy to get lost in translation.

It gets pretty funny, especially for things like text messages,” McCoin said. “With texting, one letter in and out can change the meaning by a lot.”

In order to help mediate the disorder, these students are given various accommodations, ranging from extended time on tests and essays to being allowed a computer to take notes in class.

However, these accommodations are not handed out indiscriminately.

“Students don’t qualify for classroom and testing accommodations solely based on the diagnosis,” Pechersky said. “(They qualify) based on the profile of strengths and weaknesses that we get when they have an educational evaluation.”

Unlike many schools in the U.S., St. Mark’s still enforces certain policies that challenge dyslexic learners. These policies are always made in the best interest of these students.

“We still penalize spelling errors,” Pechersky said. “We also do not exempt foreign language requirements. There are some schools that do that for students with dyslexia.”

Learning a foreign language comes awkwardly to many students with dyslexia, especially when words need to be read aloud. As a result, many dyslexic students are recommended to take Latin, where the speaking component of the language is not as significant.

“For example, in Spanish, students are reading, listening and speaking,” Pechersky said. “In Latin, students are reading and writing the language, but they’re not necessarily speaking conversationally. So while you still have to have a good foundation of grammar for Latin, some of our dyslexic students find Latin to be easier for them.”

When he was in elementary school, McCoin, disadvantaged with languages in general, was one of the few students in his grade to not learn Spanish. But dyslexia affects students in different ways. In fact, Spanish comes naturally to Hewes Lance ‘26. It’s straightforward; a phonetic language is paradise for him.

“Spanish is actually easier for me because Spanish is spelled exactly how it sounds,” Lance said. “If you can say it, you can spell it. I found that it’s easier than spelling words I don’t know in English.”

In spite of their condition, Lance and McCoin still find success at school. They just have to work twice as hard as their fellow students.

“Dyslexia just makes learning slower,” McCoin said. “It’s not impossible to do. It just takes a longer time, right?”