Graceland is one of the most popular tourist destinations in the country. The former home of the “King of Rock and Roll,” it now encompasses 200,000 square feet of museums, restaurants and gift shops. But in 1992, when Director of Libraries and Information Services Tinsley Silcox got the call to help archive and catalog Elvis Presley’s Tennessee mansion, it was nothing more than an unorganized collection of memorabilia.

Prior to coming to the school, Silcox served on the faculty of the University of Mississippi as the Director of the Blues Archives and Music Librarian, where he oversaw one of the largest collections of blues and blues-related material in the country. During Silcox’s time as director, he worked closely with the Center for the Study of Southern Culture at the university, whose goal was to teach about the American South and its culture.

“At the time, the Center was run by a man named William Ferris, who later went on to be head of the National Endowment for the Humanities,” Silcox said. “It is a graduate degree program, and that summer a young lady named Shelly had graduated with a master’s degree in Southern culture, and she was immediately hired to be the archivist at Graceland.”

Quickly, however, it became apparent that Shelly needed some extra help.

“She had zero archival experience, but she had the background knowledge of the material,” Silcox said. “Two or three months into the job, what they discovered was that they needed some that really understood archives and how to handle archival materials.”

Though the house had opened up to the public starting in 1982, just five years after Elvis’ death, family members had continued to hang out and live there. Parts of the house, like the family quarters, remained inaccessible to the public because they were still in use, but generally, the security was relaxed.

“At that time, people were coming and going regularly, and people that were distant relatives, or at least claimed to be, were coming into the house and stealing stuff,” Silcox said. “They’d take a cigarette lighter and stick it in their pocket, or they’d see his magnificent car collection and steal a cigarette lighter out of them or (even) a hubcap. Stuff was being taken at a prodigious rate.”

The responsibility of figuring out how to open everything up and in turn transform Graceland into a thriving business thus fell to the archivists.

“Shelly called me and said, ‘I’m in over my head; maybe you can be the person to come and help me,’” Silcox said. “So I went up there, and we worked together for a few weeks.”

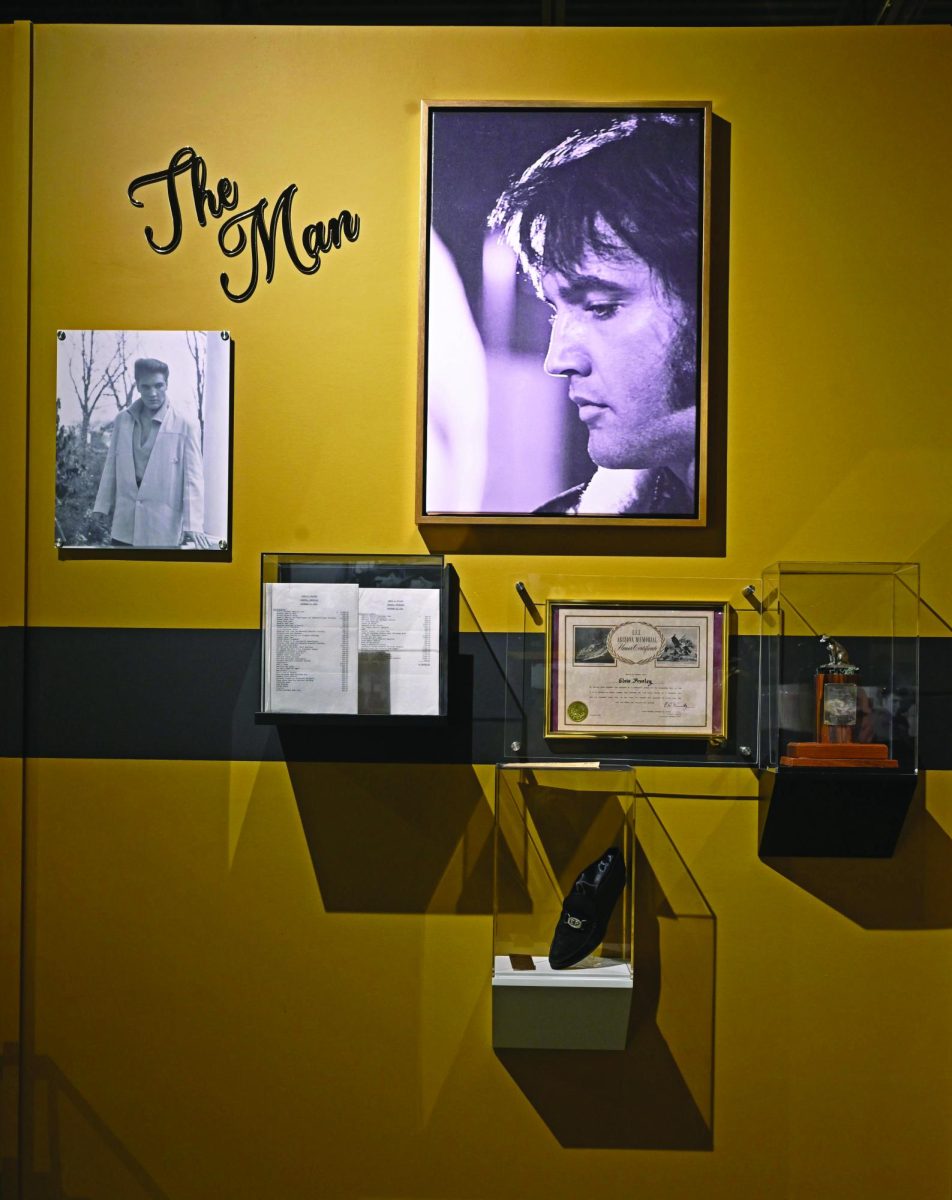

The main deliberations came over what to and what not to present, as well as how the items would be displayed. When Graceland was opened to the public, a larger space had been added to allow visitors to walk through and view things like a typical museum, though besides the addition of glass display cases there had not been many preservation efforts.

“By the time Shelly got there, there were people already touring through the spaces they had put in, and she was there to figure out how to mark all the things that were still unmarked and how to describe items,” Silcox said. “None of that had been done. They just had random stuff in random cases with spotlights on them.”

One of the exhibits had Elvis’ black wedding tuxedo and Priscilla’s wedding gown on mannequins in a glass case under spotlights. By the time Shelly and Silcox got there, the tuxedo had turned brown because of the UV light from the spotlights.

“I immediately had them turn the lights off on anything that could be affected, and ordered UV filters for everything,” Silcox said. “One of the things they had put in the cases was a copy of the Physician’s Desk Reference about drugs and drug interactions, and another was his medicine case, which just looked like a fishing tackle box with a bunch of different pills. I had them take those out.”

The cataloging process was immense: Elvis had two whole warehouses filled with furniture and other items that the archivists had to comb through. On top of that, Silcox had to order extensive repairs.

“Elvis had a hallway in which he kept all his gold and platinum records. He didn’t even take the time to hang the frames on the wall,” Silcox said. “He just nailed the records to the wall through the frame. He’d just stick it up against the wall and pound a nail into the frame so the frames were split. We had to take all of that down very carefully.”

One particularly memorable experience was opening up Elvis’s private jet. To preserve the interior of the jet, a Plexiglas cover had been installed on the door so that visitors could peek inwards.

“You couldn’t really see much because of all these dots on the Plexiglas, and I realized that those were giant moisture droplets,” Silcox said. “There was no ventilation in the plane, which was sitting in the Memphis sun. We called a company to hacksaw the Plexiglas off, and the smell was overpowering. Everything was starting to mold.”

Ultimately, after spending a couple of weeks with the faculty, Silcox left them with a list of instructions and materials to buy.

“It was one of the most interesting couple of weeks of my life,” Silcox said. “I’m so glad that I did it for a lot of reasons, but mostly because regardless of whether you like his music or not, (Elvis) was very important in American music history for a lot of reasons. Those sorts of things beg to be preserved.”

Listen to the Focal Point Podcast on

Spotify or smremarker.com