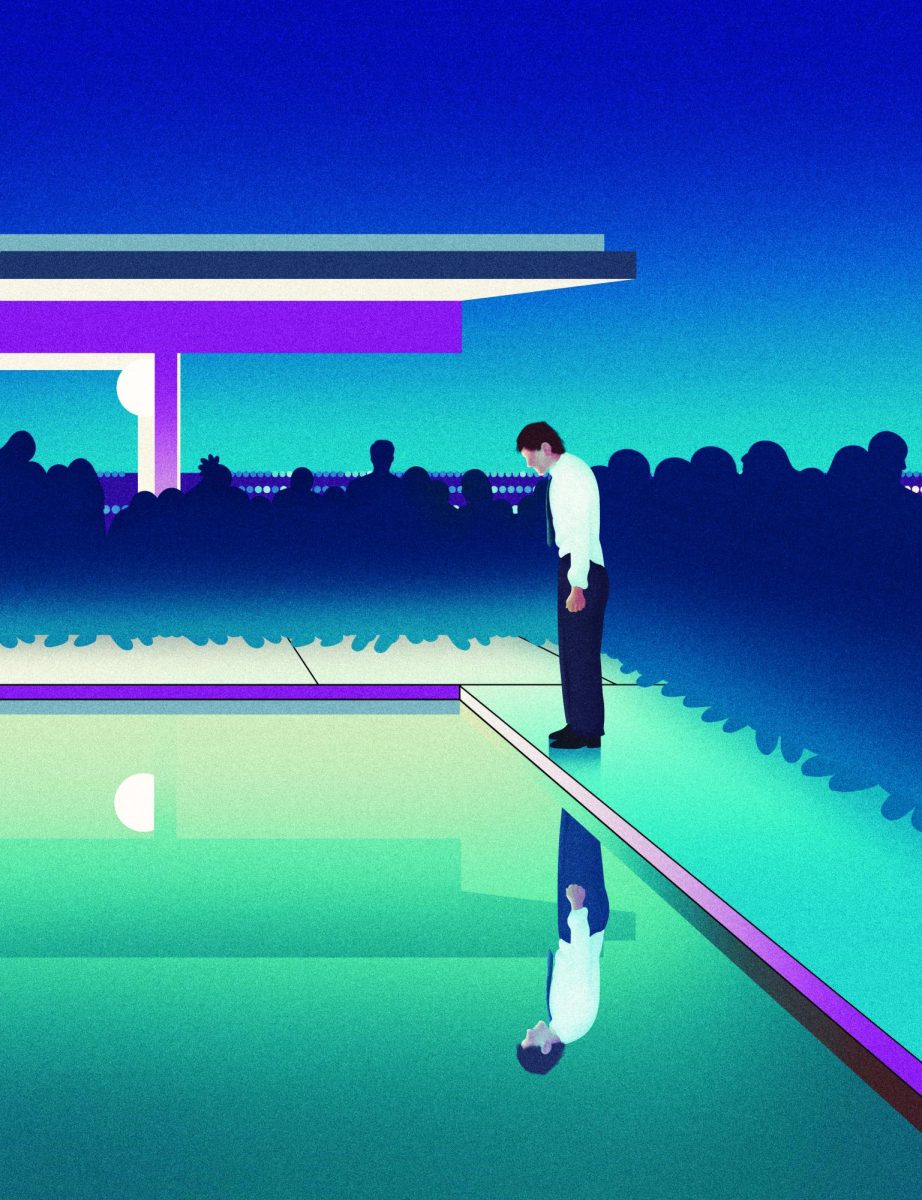

Standing on the board, looking at the water below. Even though it’s only a couple meters, it feels like standing on a cliff’s edge. Knowing the judges will critique every minute mistake you might make. Feeling the pressure that you have to succeed. But finding composure despite it all. Those old memories are coming back. For Middle School Math Instructor Liz Kraft, she knows it all too well. As one of the best divers in the country, she routinely competed at the highest level, even achieving a world first along the way. Behind her passion and great success is a story of constant dedication to the sport, from her youth to the present day.

And throughout the decades, the diving board has always seemed to find its way into her life, even when her thoughts tell her she can’t or she shouldn’t anymore. It’s a passion that chases her as much as she chases it.

“When summer comes around, I think I’m not gonna be able to do this. I’m too old,” Kraft said. “And one day, I just get out there and start bouncing a little bit, and it’s just fun. It’s kind of like flying. It’s hard to stop.”

But her journey didn’t begin here. Instead, it started when she was just nine. Inspired by divers at a competition at her local country club, Kraft taught herself a couple of dives to show off in hopes they would ask her to join their club. At the time, no proper diving programs existed in New Orleans, and diving was mostly unheard of. But, at age 11, she started to properly train, working with a local coach at Tulane University’s natatorium.

By the time Kraft reached high school, she knew diving was what she wanted to do. Driven by her passion and competitive spirit, she continued her career, participating in diving camps every summer held by the University of Michigan’s head coach and competing in many national and international events. In her senior year, Kraft committed to the University of Michigan’s diving program and joined the following year.

Adjusting to the college lifestyle was rough. The switch came with a major increase in coursework and practice time. Her college schedule revolved around her diving practices, one in the morning and one in the afternoon. Her college practices consisted of practicing spins with a belt and trampoline set up in the morning and then diving off either a 1-meter, 3 1/2-meter or a 7 1/2-meter board to practice real dives, each two hours in length. Balancing the coursework, her athletic career and her college social life was definitely a struggle, and some things had to give.

“When I arrived on campus, my coach told me there were three things to do at the University of Michigan. There was studying, there was diving, and there was partying. He told me to pick two of them and he was right. I tried to do two and a half, didn’t always work out really well. There was a huge learning curve on trying to balance time management,” Kraft said.

Eventually, all of her hard work paid off, and her performance in competitions reflected the dedication and time she put into practicing her diving. Kraft set a record as the first woman to land an inward 3 1/2 somersault on a 10-meter board.

However, her career came to a tragic halt when she dislocated her shoulder in the finals of a national competition in her senior year. Kraft was forced to redshirt for a year at Michigan and then transfer to SMU, where she had one year to get back into shape for the 1980 Olympic Trials. Not in prime shape for the trials, she didn’t move on, and without a way to continue her diving career—since college athletes weren’t allowed to be paid—she retired.

But lessons she learned from her diving career stayed with her after it ended. Even without competing anymore, the lessons on giving her all and being dedicated and passionate about what she does translate to her teaching. “To be at that level of diving, you have to be willing to put in hours that other people don’t necessarily want to, but you do it because you love it,” Kraft said. “I still see that today with my teaching. I don’t think about the number of hours that I’m putting into something. I’m doing it because I enjoy it, and I don’t usually know how to stop until it’s done.”

Though her career ended without competing in the Olympics or becoming a professional diver, Kraft has no regrets.

“I never regretted anything,” Kraft said. “People used to ask, ‘are you trying for the 1976 Olympics or the 1980?’ No, I was going for tomorrow, I really loved diving. It makes me feel good every day that I know I’d really given a lot, it all in the journey.”

An important reason for her lack of regret was a change in mindset that occurred during a session with a sports psychologist at SMU. In a room with former Olympians and national champions, Kraft came to the realization that basing happiness on awards and accolades would leave her ultimately unsatisfied.

“The sports psychologist was talking, and I was listening, thinking, ‘This is the strangest thing that I’m hearing, the people who have been to the Olympics and the national champions are no more satisfied than I was with my career.’ It hit me like a brick at that moment that there’s not going to be a point where I am satisfied,” Kraft said. “It’s really the journey and all the other things that come with it, it’s the dedication, the hard work.”

With the mindset of focusing on her journey instead of the awards, Kraft is proud of what she accomplished during her career. To her, she did what shouldn’t have been possible and got everything she could out of the sport, and that was the true reward.

“The fact that I had such a competitive spirit and a drive that was just insatiable got me to a level that was probably far beyond what I otherwise should have. I just enjoyed the sport to its fullest, and because I loved it so much, I did really well and got super close to actually going to the Olympics, which is crazy,” Kraft said. “My proudest moment is that I got more out of the sport than a lot of people who got into it because they wanted to be successful or win.”