Less than 2 percent of the world’s population possess a doctorate degree.

And less than 3 percent of high school teachers have ever taken a PhD program.

While obtaining that coveted title of “Doctor” demands an incredible amount of dedication to one’s craft, St. Mark’s boasts many passionate PhD-possessing instructors.

College graduates who wish to pursue a doctorate typically apply to several PhD programs in hopes of securing an acceptance to one of them.

These graduate school applications, with their own required letters of recommendation and standardized test scores, closely mimic current college applications.

Some programs even enforce qualifying exams to proactively weed out weaker students.

Afterwards, PhD candidates immediately dive into advanced post-graduate classes while simultaneously working on as-yet unsolved problems — this process is aptly known as “research.”

Much of a candidate’s research will eventually become part of his or her dissertation, the culmination of multiple years’ worth of hard work and deep thinking.

Once an individual earns a PhD, he or she have multiple avenues of work that they can pursue.

Some choose to continue researching as a professor — by far the most popular choice — and others choose to go into industry.

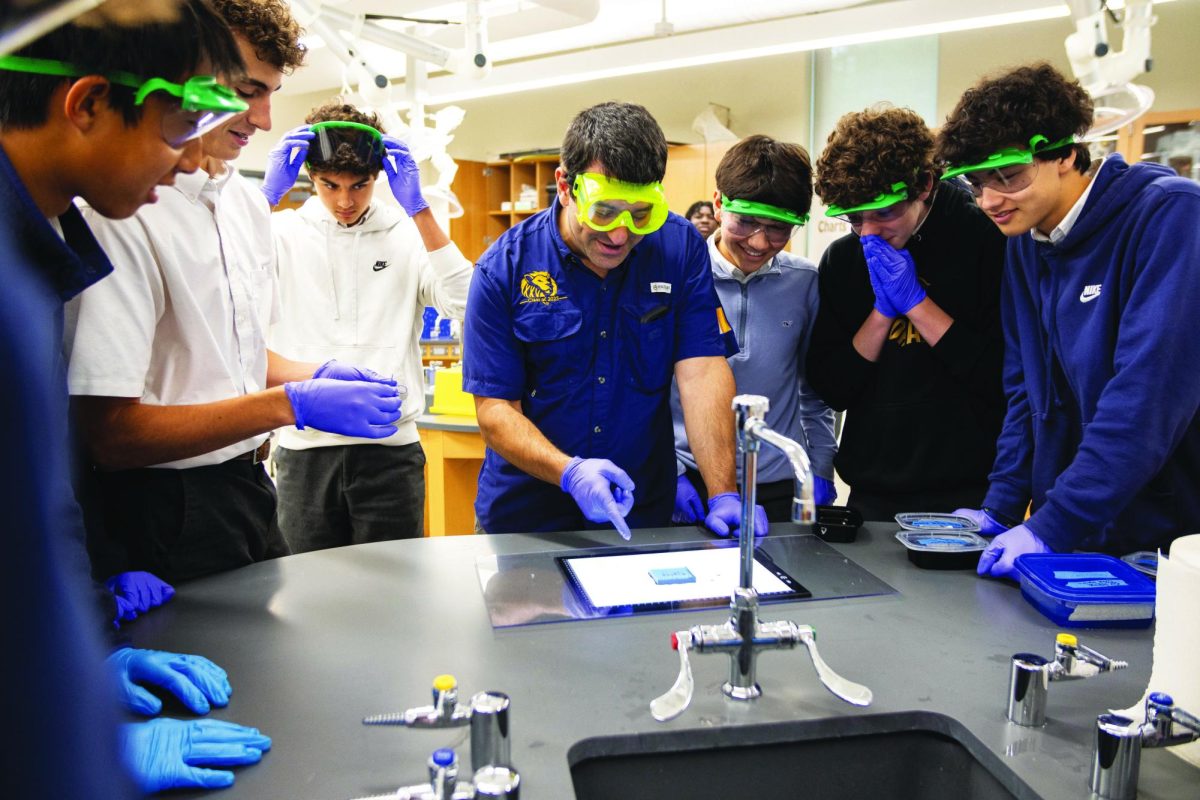

But some, like history instructor Bruce Westrate and biology instructor Dan Lipin, decide to impart their knowledge on younger generations by teaching at K-12 schools.

Westrate, who obtained his PhD from the University of Michigan in 1982, explored many different careers after finishing graduate school.

“I’ve always wanted to do something related to the study of history,” Westrate said. “Unfortunately, in the 1970s and 1980s, the job market was very poor, so I did all kinds of other jobs because I had kids. I also taught part-time; I taught at Lake Michigan University, Purdue and also at Indiana University.”

However, he eventually learned about St. Mark’s at a history seminar in Austin.

Partially driven by his kids approaching college, Westrate made the decision to move down to Dallas and apply for a master teaching position at the school, where he’s taught since then.

“The school contacted me and I flew down,” Westrate said. “They made me a nice offer, so that’s why I came down here. I didn’t have any experience in private schools like this; I didn’t know schools like this really existed, because I was raised in a small public school.”

One aspect of the school Westrate particularly enjoys is the freedom he gets to teach his students in the way he finds best.

“No one interferes with me,” Westrate said. “St. Mark’s makes its decision on you when you’re hired. Then after that, there’s very little in terms of micromanaging how you teach your class. That kind of freedom is something that you don’t necessarily get in college.”

Lipin, on the other hand, first decided to work at the pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca after earning his master’s degree.

His research at AstraZeneca mainly focused on various methods of manufacturing vaccines, but after working there for two years, he decided to leave and pursue additional higher education.

“After I graduated, it was very challenging to get a job,” Lipin said. “But my parents said, ‘why don’t you go get more education?’ And so I decided to do a PhD at the University of Queensland, Australia.”

Although Lipin originally planned to go into industry with his PhD, a side experience teaching at a summer camp opened his eyes to what he truly wanted.

Research can be hit-or-miss for many people, and some individuals genuinely enjoy the struggle of solving original problems while others find the work mind-numbing.

“I didn’t think I wanted to spend my entire life doing (research),” Lipin said. “I could and had done it, but I just didn’t think it was the thing for me. I actually worked for a summer as a counselor, and when I finished it, I said, ‘I want to become a teacher.’ And when I went for interviews, I found that I wasn’t telling them what they wanted to hear. It was coming from inside, and I knew that I had found something that was worthwhile and that I would enjoy.”

Similar to Lipin, Westrate found teaching students to be much more rewarding than his research experience, despite his success in writing research papers and bestselling books.

“Making a lasting contribution to the lives of young students is something I don’t think I would’ve found in research,” Westrate said. “Research is important, but it can be tedious, and after you publish a book, you’re just sitting around waiting on reviews. Writing these books and papers can be rewarding, but here at St. Mark’s, I get to inspire kids every single day.”

For Westrate, teaching provides him an opportunity to shape the next generation of students in a way that research could not.

“There’s nothing more fulfilling than helping young minds learn about history,” Westrate said. “Because honestly, I don’t know how they can become good citizens without knowing a little about history. And I hope I can be the one to provide that for my students.”