Stressed students abuse stimulants

She adjusted her glasses before the Ron Jackson State Juvenile Correctional Complex connected her to her third patient of the morning. She had already looked over the teenager’s symptoms and his parents’ concerns.

Difficulty listening to instructions. Does not stay organized.

Cannot focus.

A psychiatrist for more than a decade, Dr. An Dinh is well-experienced in recognizing patterns. She’s seen this very same diagnosis hundreds of times. But lately, it’s become alarmingly frequent.

She saw the signs in a patient she met with last week and again in another one she met yesterday. She double-checked the file on her laptop, making sure it wasn’t the same patient she saw earlier that morning. She felt a strange sense of déjà vu — this patient had the same symptoms, story and condition.

Another patient with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

She would probably be signing another prescription for a stimulant — for a central nervous system stimulant composed of amphetamine salts. Commonly known as Adderall.

Dinh has noticed a subtle increase in patients requesting medication to stay focused and study effectively. But it’s hard to tell if they need it or not.

After all, the patients aren’t physically in front of her; she’s diagnosing them through her 14-inch MacBook Air. It’s difficult to spot the subtle ticks, the darting eyes and the shaking legs that she would instantly catch if she wasn’t looking at the upper half of a forehead.

Dinh has met with patients who were on six psychiatric medications they didn’t even remotely need. She’s observed the overdiagnosis of ADHD. She’s held stacks of stimulant prescriptions.

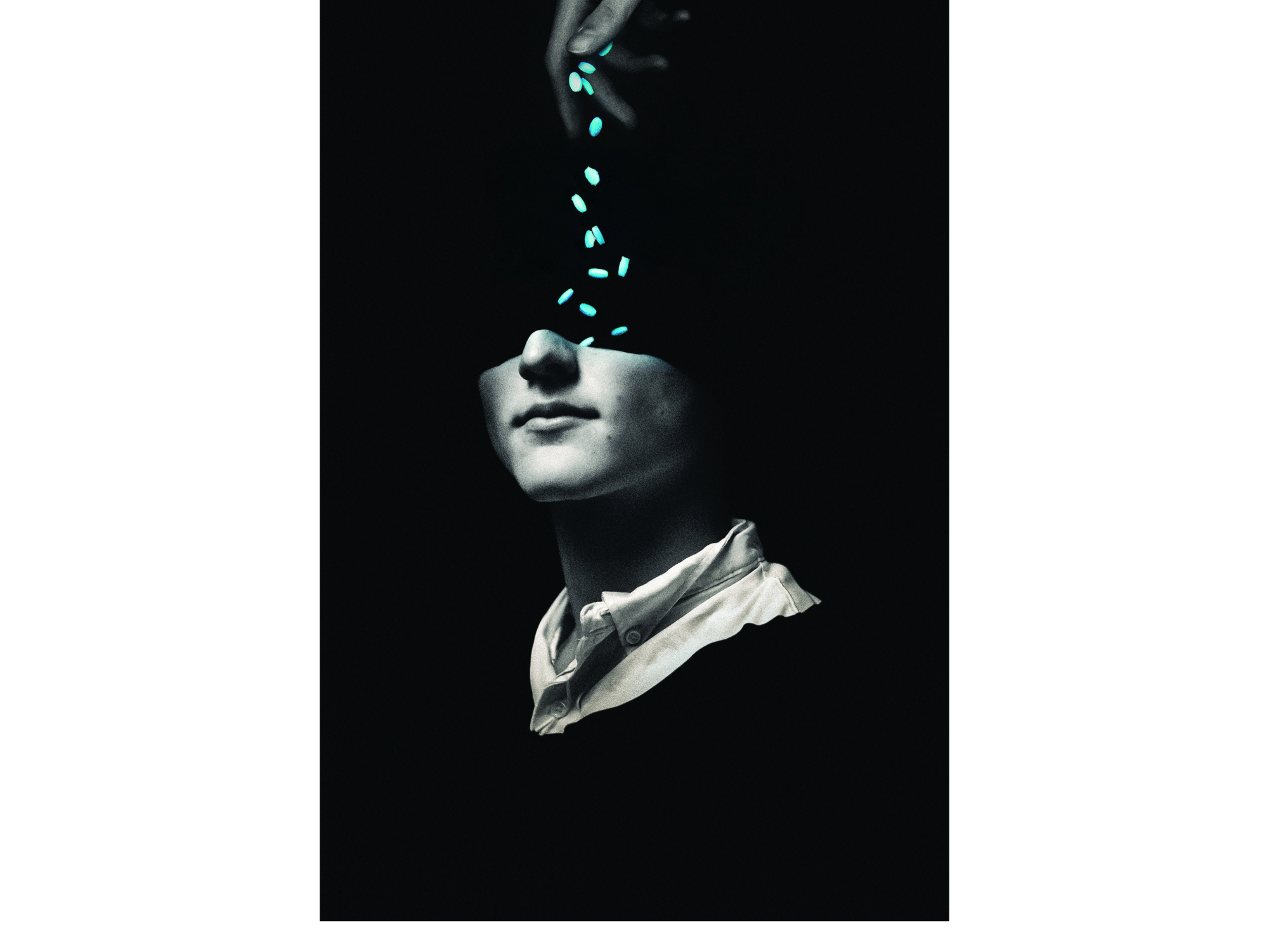

And she knows what’s going on: exhausted students turning to a small, vibrant pill for salvation — for an easy way out.

What was once a tightly prescribed pill used to combat ADHD is now a common study drug for both the prescribed and the unprescribed. A crutch, passed around like sticks of chewing gum. An addiction prevalent across campuses nationwide.

It’s May. Finals at the school are on every student’s mind. For some, it’s an opportunity to raise their grade above some threshold. For others, it’s a risk that could knock their GPAs down.

The inherent stress that comes with exams pushes students to their limits — an intended effect of its practice at schools. Late nights spent studying are a seemingly universal experience for Marksmen and students nationwide at varying schools. And, of course, students try to find a shortcut, anything to lighten their workload.

The recent increase in the usage of Adderall, in a prescribed manner, has brought attention to its effects and even bolstered its appeal. For some students, these seemingly superhuman studying abilities define its illicit usage.

“The first time I used Adderall was for sophomore year exams because I needed an ‘A’ on my chemistry final,” an illicit Adderall user who requested anonymity said. “I thought, ‘I gotta do anything I can to get this.’”

For him, it worked. Each time he took a pill, he was more focused than ever. He could tell the drug had kicked in when his vision zoomed in, he felt a little nauseous and he became obsessed with studying. He felt like his brain was moving “a million miles an hour.”

This sensation was attractive. Not procrastinating and studying for hours on end wasn’t just easy now, it was fun. While he reported a similar level of memory retention, the quality and quantity of his studying were amplified. When he started something, he couldn’t stop until he finished it. It wasn’t hard for him to see why some people get addicted to it.

Each unprescribed user has a prescribed seller. Some willingly advertise the study drug while others simply ignore this illegal market.

One prescribed user, who requested anonymity, claimed several students have approached him, inquiring about buying the drug from him. And though he doesn’t sell any Adderall, he knows how high assignments can stack up and how stressed students get during the month of finals.

“I’m not ridiculously taken aback — in fact, I completely get it,” the prescribed user said. “We’re busy at St. Mark’s. We don’t get a lot of sleep. We’re always studying. We’re hard pressed to get more done.”

Dinh recognizes the appeal of stimulants. On the surface, the short-term benefits outweigh the long-term risks.

“Stimulants are one of the medications in psychiatry that have robust results — it actually works for everybody,” Dinh said. “It improves cognition, whether you have ADHD or not.”

While taking the drug has its user-alleged benefits, experts in the medical industry caution against its unprescribed usage for studied reasons. Dr. Charles Dunlap, a pediatrician of 19 years, shines light on the opposite end of taking Adderall in anticipation of finals.

“If a student takes it improperly and he’s unable to sleep at all during finals week, he’s not going to perform well,” Dunlap said. “It could potentially cause more problems than benefits, especially if it’s not prescribed to them by their doctor.”

For the anonymous illicit user, he is wary of these consequences — swallowing the pill too late into his study session meant he would be watching the sun rise in the morning. He wouldn’t be able to stop his hands from trembling or his heart from racing.

Beyond sleep deprivation and harm, improper usage of the drug can also induce unwanted and dangerous mental conditions. Especially concerning, these symptoms that surface are often unpredictable.

“They could become labile or emotional; I’ve even seen some kids almost have depression symptoms and start crying a lot,” Dunlap said. “And that’s in situations where we actually prescribe the medicine for a kid who had ADHD, but they just didn’t tolerate it well. So we can’t predict, especially on patients who don’t have ADHD and take the meds off-label. They’re treating a condition that they don’t even have.”

Adderall, in particular, works by boosting the norepinephrine within the brain, spiking the ability of neurotransmission and thus allowing one to focus and concentrate better. This reaction is thought to be necessary to increase focus levels within a neurodiverse (irregular) brain to be comparable to a neurotypical (regular) brain.

But this chemical edge can come at a psychological cost. These effects may trigger the limbic system: the fight or flight response. In malpractice and extreme cases, the drug can lead to elevated anxiety, paranoia and hallucination. Due to Adderall’s ability to cause euphoria, the user can quickly, in most cases unknowingly, become addicted and dependent on it.

“I think unprescribed users downplay the risks; they may say to themselves, ‘that won’t happen to me,’ or have a belief that they are really in control,” Upper School counselor Dr. Mary Bonsu said.

In contrast, the frequent and, for some users, daily consumption of Adderall turns into a necessity. The adverse psychological effects occasionally seen in addicted unprescribed users are absent. Instead, most implications of the drug appear when it is not taken.

“There will be days when I’ll forget to take it,” the prescribed user said. “I get so lethargic and tired; it’s ridiculous. Within 10 minutes, I’ll feel that difference. My homework, productivity and test results will reflect that difference too.”

He questions if the cause of these effects stem from a formed dependency, tolerance, or if it is rooted in his condition.

“The issue that can arise from taking stimulants is you develop tolerance, and the same amount doesn’t work anymore,” Dinh said. “What happens when you increase the dose, then you get more side effects from it. You won’t be able to sleep, and you won’t be able to eat.”

A final side effect seen in both prescribed and unprescribed users relates to their personality in social settings, even if they don’t feel the difference is especially pronounced.

For the prescribed user, he often doesn’t feel like himself when he is not medicated.

“The social changes are ones that would traditionally be denoted as positive: less impulsive behavior, more in-line and being more attentive,” he said.

And for the illicit user, he feels off when he is on the drug.

“If somebody tries to interact with me when I was locked in and studying like when my parents would come in my room, I would snap at them and tell them to get them out of my room,” he said. “It’s not something that I would like to do outside of studying, though. When I hung out with my friends after I’d used it to study, it was pretty weird. I felt kind of dissociated from what was going on.”

Aside from its legal implications of jail time, fines and a permanent criminal record, the illicit consumption and selling of prescription drugs like Adderall can seriously affect one’s mental stability. Rather than pursuing such measures for academic performance, Bonsu recommends safer alternative methods.

“Study strategies like the deep focused practice and management of digital distractions,” Bonsu said. “Keep them as far away as you can when you are prepping, and playing it smart by looking at your grade cushion can also help.”

Caution against even accessible stimulants like caffeine should also be noted. Though students often feel the need to trudge through late nights and early mornings, all-nighters can be more harmful than helpful.

“Sleep does more for the brain than something like an Adderall does,” Bonsu said. “It just does way more because it consolidates your night’s studying and creates smooth pathways between short-term and long-term memory.”

According to Bonsu, the most dangerous part of taking stimulants is the mindset of the user. The user believing that he can’t study without the medicine is a significant indicator of the brain’s increased dependence on it. From her perspective, stimulants are like a spectrum that affects one’s alertness to their activity at hand.

“Alertness doesn’t make you smarter; it doesn’t help your recall,” Bonsu said. “It does help with working memory. That’s probably why students assume that it’s okay to take (Adderall). Executive functioning and working memory are simply the ability to temporarily hold information so that you can operate on it.”

This distinction between enhanced focus and heightened cognitive ability can become easily blurred. And in some cases, people can begin to associate any lack of concentration with a clinical issue, even though it might be temporary or situational in nature.

“Not being able to focus by itself doesn’t make you have ADHD,” Dinh said. “You really have to look at the lifelong struggles that people with ADHD have. You have to have that longitudinal lens, not just a one-time interview.”

The reliance that some grow to have on substances like Adderall without a prescription can create a false sense of productivity — a facade that masks deeper underlying issues that typically stem from lack of preparation or mounting academic pressures.

These psychological effects, which can go unnoticed, can also increase the risk of students developing a warped relationship with their academic lives, a diminishing of self-worth and capability initiated by unnecessary external substances. The danger isn’t just the pill itself — it’s the potential belief that you’re less without it.

In these situations, jumping on opportunities to take a shortcut during stressful situations can often be appealing and even seemingly irresistible, but the consequences and benefits of one’s actions should be thoroughly considered before taking such measures as participating in illicit Adderall usage.

“An easy solution is usually the most dangerous one,” Dunlap said. “You should never sacrifice convenience over safety.”

And as finals quickly approach, it’s essential to remain wary of the pill’s effects — not every restless mind needs a prescription. The true test may not be on the exam but in how students decide to prepare themselves for it.