Andrew Ye

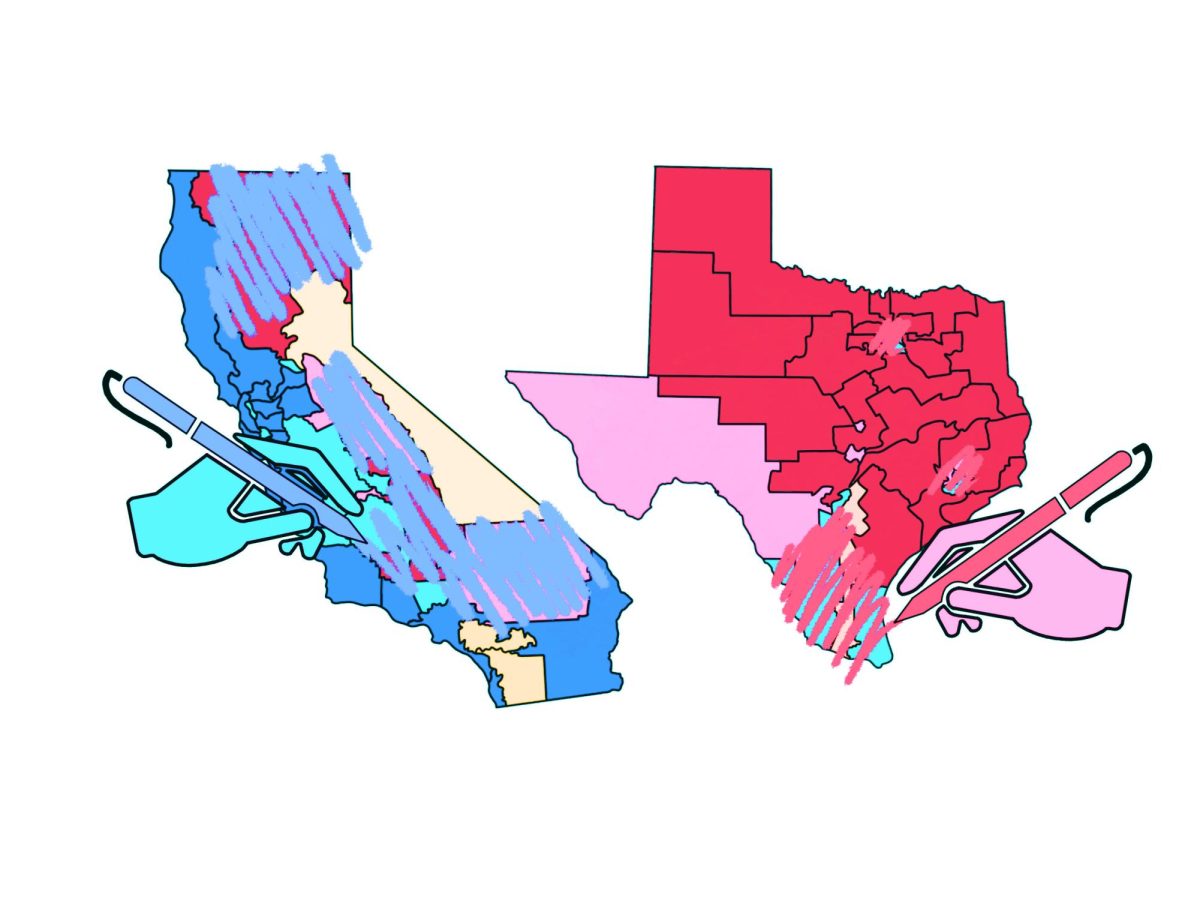

Every 10 years, states can choose to redraw their boundaries in the act of redistricting.

At 219-213, Republicans hold only the slightest edge in the House of Representatives, which is effectively deadlocked. With the 2026 midterm elections, just one more seat for either party could completely flip the House on its head.

Now, Republicans and Democrats are scrambling to flip districts whenever possible, and Texas’ new redistricting bill has sparked conflict between the two parties.

Signed into law on Aug. 29, Texas is projected to gain a total of five Republican seats. That shift would split the House by a whole 10 districts. In retaliation, California has proposed a bill that would heavily favor Democrats, splitting up different voters into different districts based on their voting direction.

But both states may have crossed a line, setting a dangerous example. Through gerrymandering, these bills are eroding voter power, enabling congressional seats to be determined by the party in power rather than by voters.

“Gerrymandering is the unnatural division of voting districts,” History and Social Sciences Department Chair David Fisher said. “It’s a situation where politicians are choosing their voters, as opposed to voters choosing their politicians.”

Redistricting is meant to be a natural event when it occurs every 10 years after census data comes out. But when redistricting skews the political balance too far in favor of one party, it’s considered gerrymandering.

“There’s a definite effort to use the way districts are gone to give the maximum advantage to that party that’s in power,” Jeffrey Dalton, founder of Democracy Toolbox, a political consulting firm, said.

Gerrymandering comes in two forms: cracking or packing. When officials redistrict to favor one party, they can either carve pieces out of existing districts, shoving voters into a district where they are the minority, or pack all of the voters of one party into one district, minimizing the number of representatives they get.

In Texas, the government is redistricting in the middle of the decade, as opposed to the usual 10-year period.

“We’re in the middle of a midterm backlash year where typically the party that owns the White House will lose somewhere else,” Dalton said. “So this is a preemptive effort to mitigate the midterm effects.”

Currently, the Democrats need to flip three districts to gain power.

And because of the tight race in the House of Representatives, Texas’ gerrymandering has created ripples across the entire U.S., leading to California’s decision to pursue the same course of action, but this time to increase the number of Democratic seats in California.

“So the reaction in other states where Democrats have more power is, ‘Okay, well, if they’re going to do it in Texas, we have to do it here as a counter move,’” Dalton said. “It’s like a bunch of dominoes falling over.”

Gerrymandering, as it is being enacted currently, is a bipartisan issue — both sides know that it’s not necessarily fair. However, as Gavin Newsom, Governor of California, puts it, both parties must “fight fire with fire.”

Gerrymandering doesn’t break any laws. However, if more and more states start replicating Texas and California’s behavior in retaliation, races can become predetermined, and voters will be pushed and shoved around.

“What’s just happened in Texas or what will happen in California for instance, will be perfectly within the law,” Fisher said. “But it is messing with the spirit of what we want — a rules-based democratic order in which your vote counts.”

Fisher believes that because of the lack of representation in government and the lack of value in an individual’s vote, gerrymandering creates a system in which democracy is slowly being destroyed.

“If we want citizens to have a say in government, we should be opposing gerrymandering,” Fisher said. “We should be agitating for some other system that is fairer, more democratic and more politically effective.”

Part of the issue is the party-affiliation within redistricting committees. And even for non-party-affiliated redistricting committees, the party in power can gerrymander in their own favor, simply by brute force.

For Dalton, gerrymandering comes down to one core issue — a lack of checks and balances in the redistricting committees.

“In states where raw power determines the district drawing, there’s really nothing you can do other than for the party out of power to win more elections,” Dalton said. “We used to have checks and balances — those have been eroded and don’t exist to any great degree anymore.”

Currently, both parties are adding fuel to the flame to an issue detrimental to democratic principles. However, non-partisan redistricting committees that integrate checks and balances could be the blanket that smothers the fire — if both sides agree to cross the aisle together on the issue of gerrymandering.