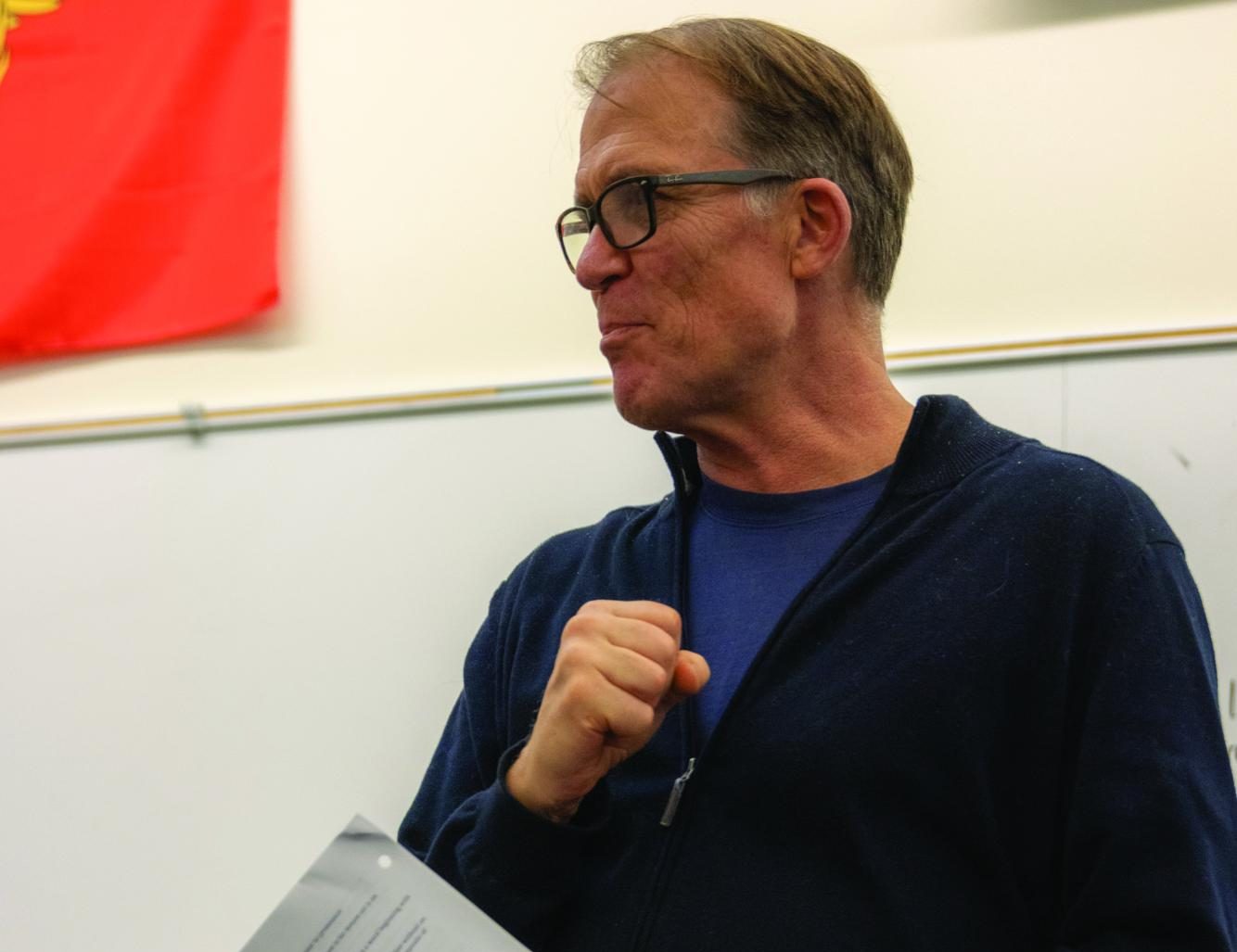

Latin instructor David Cox is no stranger to adventure.

As a broke, thrill-seeking 20-year-old, he knew he needed something to jumpstart his life and give him a new view of the world.

But Cox did not follow the traditional path of a young man in search of meaning. Instead, he traveled across the country to Alaska.

His time there, filled with crazy tales of rough seas, wild bears and strange men, changed his life forever.

Cox made the decision to venture to Alaska with a friend spontaneously.

“I was 20 years old, and I was kind of a romantic,” he said. “I had read Moby Dick that year in college and I thought it was time for me to have my Ishmael experience.”

By hitchhiking and riding buses and planes, the duo made their way to the town of Sitka, Alaska. With a population of around eight thousand, Sitka is just outside the top 10 largest cities in the state.

“The town of Sitka is mainly one road on an island that is probably 10% inhabited,” Cox said. “The rest of it is deep, old forests, pine trees that you can’t reach around. We stayed in a camp that was all the way out at the end of this road.”

At first, Cox took a job as a taxi driver to make ends meet. While he spent most of his time shuttling drunk locals around in the early hours of the morning, one particular customer was different from the rest.

“Usually, they were friendly and sat in the front or in a seat where they could talk to me,” Cox said. “This guy sat right behind me, which was weird. And then, as I was driving back into town, the dispatcher’s voice came on and said,

‘Hey, Dave, be careful out there. Some guy’s got a knife, and he’s been slashing tires.’ And I knew the guy behind me was that dude.”

Not sure if the man would move from slashing tires to thraots, he slammed on the brakes and jumped out of the car. Simultaneously, three police cars rounded the corner, grabbed the man and brutalized him.

About a week after the terrifying encounter, a German man named Helmut offered him a new job on an old fishing boat. He accepted immediately, as fishing was what he dreamed of when he imagined a new life in Alaska. Quickly, he realized that the fishing life was anything but glamorous.

“The captain assured me that it was safe,” Cox said. “He told me we had survival suits on the boat, but I never knew where they were.”

Cox went into the halibut fishing business and spent his first day at sea learning how to all kinds of knots.

“The entire time I was thinking, ‘this isn’t so bad,” but what I didn’t realize is we were going up what’s called the inside channel, between all these barrier islands,” Cox said. “It was almost like going up a river. Helmut suddenly cut between two islands and we were right on the high seas. I spent the next 24 hours puking my guts out.”

The experience was so traumatic that Cox considered jumping overboard and swimming to land, a thought that was quickly extinguished when he recalled the frigid water temperatures that would cause hypothermia in 30 minutes. After a while, Helmut made the inexperienced sailor force down a potato dish and chew some tobacco, and Cox’s seasickness vanished.

After the brutal period of seasickness, Cox believed the rest of the journey would be smooth sailing. Instead, he was introduced to one of the most dangerous jobs in the world – halibut fishing. At first, Cox worked a job that involved handling fast, sharp hooks that could carry an unwitting sailor into the ocean below. After a few harrowing days, he was lucky enough to be tasked with gutting the fish, a much safer job. Cox soon learned that only a certain kind of person could thrive during halibut season.

“My shipmates were all a little crazy,” he said. “You’ve got to be a little crazy to be a fisherman anyhow. As I was cutting a fish, he reached in and ripped out the heart, still beating, and swallowed it whole. He said, ‘You dare me?’ And I said, ‘Yeah.’ He didn’t ask for money or anything. He just popped it in his mouth and swallowed it.”

Cox eventually returned to the lower 48 states, hitchhiking back down the western coast of America. Eventually, he landed a job as a teaching intern at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts. After a few other teaching tenures, he arrived here.

Growing up near Canada, Cox’s first experience with language studies came in an elementary school French class. When he entered high school, he decided to add another language to his lexicon, and he started to learn Latin. Even though Cox loved the study of Latin, his career as a Latin teacher almost ended before it even began.

“I went off to college thinking I would go into engineering,” he said, “so I took the entry-level calculus classes. And it was my worst academic experience. The teacher was so bad—this is an Ivy League school, by the way—that kids either dropped out or stopped going, and I was one of them. I couldn’t understand what he was saying. I couldn’t understand his instruction at all.”

In order to pass that calculus class, students needed to receive at least grade of at least 60. Cox finished the year with a 61.

“Yeah, it came right down to the wire,” he said.

While Cox struggled through derivatives in that introductory calculus class, he found solace in a small, engaging Latin course.

“The teachers remembered me, they addressed me by my name, they would have a party for the class at the end of the year, and I thought, ‘These people are civilized.’”

After deciding to focus on Latin, Cox never looked back.

Throughout his life, one piece of advice has kept him afloat and given him the strength to pursue his goals.

“I went through a tough time when my first marriage did not work out,” he said. “I was down in the dumps. And my father, who was a very literary guy, sent me a very supportive letter with a quotation from Emerson.”

Emerson stated that he admires the kid from Vermont rather than a Harvard graduate who has gone to the best schools and had enormous support all his life.

“Emerson always preferred the farmer who’s done it all and failed at everything, and always like a cat, he lands on his feet,” Cox said. “You don’t necessarily have to have your life carefully planned out and programmed. Even after really difficult failures, you’ve got to keep believing in yourself, being able to bounce back from disappointment and to be resourceful and also to sort of try new things. Maybe you didn’t win this time, but you will the next time.”